Home » Posts tagged 'Labour Party'

Tag Archives: Labour Party

Labour, immigration and Enoch Powell

Introduction

In an earlier blog, we saw how working parties were set up after the Second World War whose task was to justify racist immigration controls.[1] They repeatedly failed to do so, but they continued their efforts for 17 years. Finally, employing a series of manifestly false arguments, the Tories passed the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962, complete with racist controls.

Hostility to black Commonwealth immigrants, however, was not confined to the Tories. It was, after all, the Labour government elected in 1945 that set up the working parties in the first place. Kieran Connell writes of “the relentless presence of racism in 1940s Britain, and the related influence of ideas about race.”[2] Labour was part of that pressure and influence. In 1946, Labour Home Secretary Chuter Ede told a cabinet committee that when it came to immigration he would be much happier if it “could be limited to entrants from the Western countries, whose traditions and social backgrounds were more nearly equal to our own.”[3] When the Empire Windrush arrived in 1948 with 492 Jamaicans ready to work to rebuild post-war Britain, 11 Labour MPs wrote to Prime Minister Clement Attlee, notifying him of “the fact that several hundred West Indians have arrived in this country trusting that our government will provide them with food, shelter and employment.” They feared that “their success might encourage other British subjects to follow their example.” This would turn Britain into

an open reception centre for immigration not selected in relation to health, education and training and above all regardless of whether assimilation was possible or not … An influx of coloured people domiciled here is likely to impair the harmony, strength and cohesion of our public and social life and cause discord and unhappiness among all concerned.[4]

Attlee replied to the letter, reassuring them that “if our policy [of unrestricted immigration] were to result in a great influx of undesirables we might, however unwillingly, have to consider modifying it.”[5] Kenan Malik notes that this exchange of letters contains many assumptions that shaped official and popular attitudes to post-war black immigration:

There are two kinds of British citizens: white people and “undesirables”. Britain is in danger of being swamped by immigrants taking advantage of the nation’s generosity. Immigrants’ standards of “health, education and training” are lower than those of British people. Black people are incapable of assimilating British culture. A large black presence in Britain would create social tensions.[6]

Such attitudes didn’t end with that decade but continued through the 17 years to 1962. At first, therefore, it seems puzzling that Labour opposed the 1962 Act throughout its passage through parliament. It did so, however, in the context of the ending of British rule in countries that were previously part of the British Empire and were now becoming independent nations. Britain’s post-war determination to justify immigration controls against black immigrants now came up against its need to build Commonwealth institutions and keep a political and economic foothold in the countries it once ruled. To that end, the Commonwealth was increasingly promoted as a “family of nations”. Any suggestion that the racism that had served British interests “out there” in the old Empire might now be applied to citizens of the new Commonwealth when they came here could threaten the whole project. This was a dilemma for both the main political parties. Lord Salisbury (Lord President of the Council and Tory Leader of the House of Lords) was a strong advocate of immigration controls. When a working party reported that there was no evidence that black immigrants were more inclined to criminality than white natives, he roundly declared in 1954: “It is not for me merely a question of whether criminal negroes should be allowed in … it is a question of whether great quantities of negroes, criminal or not, should be allowed to come.”[7] Lord Swinton (Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations) agreed but warned Salisbury of the dangers ahead: “If we legislate on immigration, though we can draft it in non-discriminatory terms, we cannot conceal the obvious fact that the object is to keep out coloured people.”[8] Other Tories were more cautious. Henry Hopkinson, Minister of State at the Colonial Office, declared: “We still take pride in the fact that a man can say civis Britannicus sum [I am a British citizen] whatever his colour may be and we take pride in the fact that he wants to and can come to the mother country.”[9] In 1958, Arthur Bottomley, on Labour’s front bench, had also spoken up for the new Commonwealth and against immigration controls:

The central principle on which our status in the Commonwealth is largely dependent is the “open door” to all Commonwealth citizens. If we believe in the importance of our great Commonwealth, we should do nothing in the slightest degree to undermine that principle.[10]

It seemed for a while as if the battle between racist immigration controls, espoused by both parties, and the Commonwealth ideal of a “family of nations”, also espoused by both parties, might be won by the Commonwealth. But when Labour won the 1964 general election, the new government immediately refocused on immigration controls and increased the restrictions in the 1962 Act. In the years to come, Labour would introduce legislation and rules to reduce black immigration whenever it got the chance.

Facing both ways

Labour in government dealt with the embarrassing contradiction between racism and the “Commonwealth ideal” by facing both ways and hoping nobody would notice. It constantly sought to reassure voters that it “understood” their “genuine concerns” about immigration and enacted increasingly restrictive immigration laws. At the same time, it denied being racist and passed legislation aimed at creating “good race relations”. What often emerged from this process, however, were weak race-relations laws, suggesting that the government’s priority was to curb immigration. Thus, the Race Relations Acts of 1965 and 1968 were half-hearted affairs. While the 1965 Act did prohibit “incitement to racial hatred”, when it came to discrimination it didn’t include discrimination in housing and employment, and it didn’t apply to the police; and while the 1968 Act went further and included discrimination in housing and employment, the government decided that this would not apply to the police, who had exerted strong pressure on the cabinet not to include them. Home Secretary James Callaghan told the cabinet at the time:

The opposition of the Police Federation to amending the [police disciplinary] code has been intense and deep-seated. And the Police Advisory Board has been unanimous in advising me not to proceed.[11]

In 1968, the government introduced a new Commonwealth Immigrants Act which seemed set to undo the limited good the two Race Relations Acts had done. The Act refused all Commonwealth immigrants entry into the UK unless they could prove they were – or one of their parents or grandparents was – born, naturalised or adopted in the UK, or unless they were otherwise registered in specified circumstances as UK citizens.[12] This meant that citizens in the “white” Commonwealth (Canada, Australia, New Zealand) were not refused entry. The Act was Labour’s response to the Kenyan Asians crisis, when racism on the far right of the Tory Party was at its most virulent and dangerous. It was a decision to follow the Tory racists.

The Kenyan Asians: race, nation and the end of Empire

The Kenyan Asians were being forced out of Kenya by its government’s Africanisation policy, which excluded Kenya’s Asian population from employment and other rights. Many of them had British passports, which a British Conservative government had allowed them to retain following Kenya’s independence in 1963. Now, not surprisingly, they expected to be able to use them. The Labour government, however, decided otherwise. 80,000 of them, out of a total of about 200,000, had arrived in Britain by early 1968 and the government had been under pressure from several directions to keep them out. A campaign against allowing them to enter the country was launched by Tory MPs Duncan Sandys and Enoch Powell. Sandys had already told the Conservative Party Conference in 1967:

We are determined to preserve the British character of Britain. We welcome other races, in reasonable numbers. But we have already admitted more than we can absorb.[13]

Now Powell set about raising the temperature: he used deliberately provocative and racist language. He claimed a woman had written to him (anonymously, Powell alleged, out of fear of reprisals if her identity became known) claiming abuse by “Negroes”. She had, according to Powell’s story, paid off her mortgage and had started to let some of the rooms in her house to tenants; but she wouldn’t let to “Negroes”:

Then the immigrants moved in [to the neighbourhood]. With growing fear, she saw one house after another taken over. The quiet street became a place of noise and confusion. Regretfully, her white tenants moved out … She finds excreta pushed through her letter box. When she goes to the shops, she is followed by children, charming, wide-grinning piccaninnies.”[14]

Powell declared:

Those whom the gods wish to destroy, they first make mad. We must be mad, literally mad, as a nation to be permitting the annual inflow of some 50,000 dependants, who are for the most part the material of the future growth of the immigrant-descended population. It is like watching a nation busily engaged in heaping up its own funeral pyre.[15]

The British Empire, which Powell had supported, was no more. Its former subjects had fought for, and won, their independence. Satnam Virdee argues that, for Powell,

Black and Asian workers had now become the unintended reminder of peoples abroad who wanted nothing to do with the British Empire. And, in the mind of Powell, this invited the question, “What are they doing here in Britain?”[16]

For Powell, they “represented the living embodiment of the Empire that now was lost, a painful and daily reminder of [Britain’s] defeat on the world stage.”[17] For that reason, as well as his nightmare that the “immigrant-descended population” would lead to a “funeral pyre”, he was in favour of their repatriation (or, as he put it, their “re-emigration”) to the countries they or their parents had come from:

I turn to re-emigration. If all immigration ended tomorrow, the rate of growth of the immigrant and immigrant-descended population would be substantially reduced, but the prospective size of this element in the population would still leave the basic character of the national danger unaffected.[18]

The way to solve this problem was through “the encouragement of re-emigration”. Powell noted that no such policy had been tried, so there was no evidence from which to judge potential success or failure: “Nobody knows,” he said. So he once again called his constituents in aid to support him:

I can only say that, even at present, immigrants in my own constituency from time to time come to me, asking if I can find them assistance to return home. If such a policy were adopted and pursued with the determination which the gravity of the alternative justifies, the resultant outflow could appreciably alter the prospects.[19]

The leader of the Tory opposition, Edward Heath, sacked Powell from the shadow cabinet after the speech. But there were demonstrations in support of Powell in the immediate aftermath of the speech and his sacking. There were strikes by thousands of workers. They began in the West Midlands, where Powell’s constituency was located. Construction workers and power workers struck in Wolverhampton and Birmingham, there were strikes in Coventry and Gateshead. Then they spread to the London docks and the meat porters of Smithfield market. Strikers marched “from the East End to Westminster carrying placards reading ‘Don’t knock Enoch’ and ‘Back Britain, not Black Britain’.”[20]

But Powell remained sacked. His intervention was not welcomed by mainstream politicians in the Tory party, Labour or the Liberal Party. For one thing, his provocative racism seemed likely to threaten Britain’s social stability if unchecked. Moreover, good relations with the independent countries of the Commonwealth were still deemed vital to British interests: Powell’s racism not only threatened stability at home, it endangered good and profitable relations abroad. Nevertheless, there were some in official circles who seemed to believe that government promises to its citizens could be broken with impunity. Eric Norris, the British High Commissioner in Nairobi, was against allowing the Kenyan Asians in and he watched them as they queued outside his office demanding that the British government keep its promises and honour its commitments: “They all had a touching faith”, he later said scornfully, “that we’d honour the passports that they’d got.”[21] There had been still other pressures on the government: the far-right National Front – whose preoccupations were, like Powell’s, with white British identity and the repatriation of black and Asian immigrants – were stirring in the same pot. But the government could have resisted these pressures. The liberal press, churches, students and others opposed the campaign against the Kenyan Asians and could have been called in aid. Instead, it joined the Tory racists. Home Secretary James Callaghan wrote a memo to the cabinet:

We must bear in mind that the problem is potentially much wider than East Africa. There are another one and a quarter million people not subject to our immigration control … At some future time we may be faced with an influx from Aden or Malaysia.[22]

The Act was passed in 72 hours. It met Callaghan’s wider fears, and it rendered the Kenyan Asians’ passports worthless. No wonder that a year later The Economist declared that Labour had “pinched the Tories’ white trousers”.[23]

[1] By Hook or by Crook – Determined to be Hostile: https://bobmouncer.blog/2025/05/04/__trashed-2/

[2] Connell, Kieran (2024), Multicultural Britain: A People’s History, C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd., London, p. 46.

[3] Cited, ibid., p. 20.

[4] Cited, Malik, Kenan (1996), The Meaning of Race: Race, History and Culture in Western Society, Macmillan, Basingstoke, p. 19.

[5] Cited, ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Carter, B., Harris, C. & Joshi, S. (1993), “The 1951-55 Conservative Government and the Racialization of Black Immigration”, in James, W. & Harris, C. (eds), Inside Babylon: the Caribbean Diaspora in Britain, Verso, London, p. 65.

[8] Spencer, I. (1997), British Immigration Policy since 1939: the Making of Multi-Racial Britain, Routledge, London, p. 64.

[9] Hayter, T. (2000), Open Borders: the Case against Immigration Controls, Pluto Press, London, p. 44.

[10] Foot, P. (1968), The Politics of Harold Wilson, Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, p. 251.

[11] “Callaghan: I was wrong on police and race”, BBC News, 8 January 1999: BBC NEWS | Special Report | 1999 | 01/99 | 1968 Secret History | Callaghan: I was wrong on police and race

[12] Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1968, s. 1 (2A).

[13] Playing the Race Card, 24 October 1999, Channel Four Television, London.

[14] Palash Ghosh, ”Enoch Powell’s ’Rivers of Blood‘ Speech”, International Business Times, 14/6/2011: Enoch Powell’s “Rivers of Blood” Speech (FULL-TEXT) | IBTimes

[15] Ibid.

[16] Virdee, S. & McGeever, B. (2023). Britain in Fragments: Why things are falling apart, Manchester University Press, Manchester, p. 71.

[17] Ghosh, op cit.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Virdee, S. & McGeever, B. (2023). Britain in Fragments: Why things are falling apart, Manchester University Press, Manchester, pp., 72-74.

[21] Playing the Race Card, 24 October 1999, Channel Four Television, London.

[22] Cited, Hayter, T. (2000), Open Borders: the case against immigration controls, Pluto Press, London, p. 53.

[23] Cited, ibid., p. 51.

The hostile environment: Labour’s response

In the first blog in this series (https://bobmouncer.blog/2025/03/22/hostile-environment-the-windrush-scandal-i/), I showed how the announcement of a “hostile environment” for migrants by UK Home Secretary Theresa May in 2012 led to suffering and trauma for thousands of people, the Windrush generation. In the second blog (https://bobmouncer.blog/2025/03/26/hostile-environment-the-windrush-scandal-ii/), I told the story of Hubert Howard, who was one of its victims. In the third blog (https://bobmouncer.blog/2025/03/30/hostile-environment-the-windrush-scandal-iii/), I showed how documents that could have prevented the disaster to Hubert and thousands of others were deliberately destroyed; I described how the scandal slowly emerged and the government’s obstinate refusal to roll back on the policy; and I showed how a compensation scheme was finally devised and how it failed so many Windrush victims. In the last blog (https://bobmouncer.blog/2025/04/02/hostile-environment-the-mediterranean-scandal/) I described the Mediterranean scandal, in which the EU, including the UK, stopped rescue operations in the Mediterranean and how a UK government tried to deny its responsibility for the ensuing tragedy.

In this blog, I examine Labour’s response to the hostile environment.

Labour’s response

The two major scandals examined in my previous blogs in this series unfolded, first, under a Tory/LibDem coalition government and then under the subsequent Tory government. But what was Labour’s response to May’s hostile environment? Maya Goodfellow describes it as “the most minimal resistance”.[1] Labour, the official opposition, abstained in the final Commons vote on the Immigration Bill. Sixteen MPs voted against it, but only six of them were Labour MPs: Diane Abbott, Kelvin Hopkins, John McDonnell, Fiona Mactaggart, Dennis Skinner and Jeremy Corbyn. Corbyn said the Bill was

dog-whistle politics, the mantras being that every immigrant is an illegal immigrant who must somehow be condemned, and that immigration is the cause of all the problems in our society … If we descend into a UKIP-generated xenophobic campaign, it weakens and demeans all of us and our society, and we are all the losers for that.[2]

One of the other MPs was Sarah Teather, a LibDem MP and former minister, who had told The Guardian in 2013 that the proposals in the Bill were “hewn from the same rock” as earlier welfare cuts, much of which were “about setting up political dividing lines, and trying to create and define an enemy”.[3] But apart from the six rebels, Labour MPs obeyed their leader, Ed Miliband, and the Labour whips, and abstained in the Commons vote.

By October, Miliband had moved further right. In a by-election campaign in the Rochester and Strood constituency, which UKIP was hoping to win, Miliband declared he would toughen immigration policy if Labour won the general election in May the following year.[4] Echoing Theresa May, he raised familiar spectres and fears about immigration, ignoring its advantages. The UK, he said, “needs stronger controls on people coming here” and promised a new immigration reform Act if he became Prime Minister. His message was:

- If your fear is uncontrolled numbers of illegal migrants entering the country, Labour will crack down on illegal immigration by electronically recording and checking every migrant arrive in or depart from Britain

- If your fear is of widespread migrant benefit fraud, Labour will make sure that benefits are linked more closely to workers’ contributions

- If the spectre that haunts you is, as Margaret Thatcher had put it, that immigrants were bringing an “alien culture” to Britain, Labour understands, and will ensure that migrants integrate “more fully” into society

- Miliband turned his attention to the EU. Arguments about Britain’s EU membership were coming to a head at this time, with both the Tory right and UKIP agitating for the UK to leave. In 2013, Prime Minister David Cameron had agreed to renegotiate Britain’s terms of membership. The renegotiation would be followed by an in/out referendum to take place after the 2015 general election. Miliband, in his by-election speech in 2014, included migration from the EU in his new immigration promises. He claimed that Labour under Tony Blair had wrongly opened the UK to Eastern Europeans when their countries had joined the EU in 2004. He would not let that happen again. If he won the 2015 election, there would be longer “transitional controls” for new EU members before they could move to Britain.

He even told the voters of Rochester and Strood that they didn’t need to vote for UKIP to get these policies: Labour would do the job.

One pledge seemed at first sight to be protective of migrants. Miliband said he wanted to ensure that migrants were not exploited by employers. However, this was, in fact, a reference to another fear – that migrant workers undercut native workers’ wages because bosses often pay lower wages to migrants (often below the minimum wage). However, where this problem exists, its solution lies not in immigration law but in employment law and its enforcement. It also lies in union recognition and legally binding agreements.

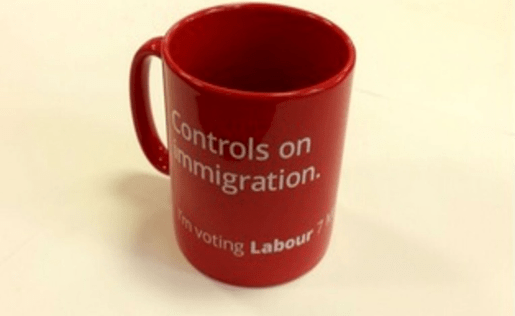

As promise followed promise and pledge followed pledge, Miliband began to sound like Theresa May. A few months later, as the 2015 election approached, Labour’s campaign included the issuing of mugs with “Controls on immigration” printed on them.

Labour’s immigration controls mug

None of this saved Miliband or his party, and the Tories won the 2015 election; the referendum vote in 2016 in favour of leaving the EU led to David Cameron’s resignation as Prime Minister; he was succeeded by Theresa May; Ed Miliband resigned as Labour leader; Jeremy Corbyn was elected in his place; the process of leaving the EU began. In 2017, Theresa May called another general election, hoping to increase her majority. In the event, the Tory party lost its small overall majority but won the election as the largest single party. But from then on it had to rely on Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) votes to get its business through the Commons.

These parliamentary changes meant nothing for the Windrush generation. The scandal began to come to light in 2017 but their suffering continued beyond the end of the decade, one of the main reasons being that the compensation scheme was seriously flawed. This remained a problem in April 2025, almost a year after the election of a Labour government. The Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman (PHSO), Rebecca Hilsenrath, had found that

further harm and injustice are still being caused by failings in the way the scheme is working. We found recurrent reasons for this, suggesting these were not one-off issues but systemic problems.[5]

In response, the Home Office sought to give some reassurance:

This government is committed to putting right the appalling injustices caused by the Windrush scandal and making sure those affected receive the compensation they rightly deserve.[6]

Nevertheless, given the Home Office’s record, we should hesitate before we are reassured. In 2020, the Williams review of the Windrush scandal had made 30 recommendations to the government, all of which were accepted by Priti Patel, Tory Home Secretary at the time. In January 2023, the Home Office unlawfully dropped three of them.[7] Moreover, the department prevented the publication of a report prepared in response to the Williams Review. Williams had said that Home Office staff needed to “learn about the history of the UK and its relationship with the rest of the world, including Britain’s colonial history, the history of inward and outward migration and the history of black Britons.” As a result, the Home Office commissioned an independent report: The Historical Roots of the Windrush Scandal. In the words of Jim Dunton, the report

lays much of the blame for the Windrush scandal on essentially racist measures introduced to restrict the ability of Commonwealth citizens to move to the UK in the years since the second world war.[8]

The report has been available internally since 2022 but, writes Dunton, “the department resisted attempts for it to be made publicly available, including rejecting repeated Freedom of Information Act requests and pressure from Labour MP Diane Abbott.” Then, in early September 2024, after a legal challenge was launched,

a First Tier Tribunal judge ordered the document’s publication, quoting George Orwell’s memorable lines from 1984: “Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past.”[9]

So the Home Office, reluctantly, made the report publicly available, and I will refer to its findings in future blogs. But it is not yet time to take Home Office reassurances at face value. Or Labour’s reassurances, come to that.

In future blogs: more on Labour’s record on immigration and race; and the necessary exposure of a long-standing myth.

[1] Goodfellow, M. (2019), Hostile Environment: How immigrants became Scapegoats, Verso Books, London, loc. 167.

[2] Jack Peat, “Just 6 Labour MPs voted against the 2014 Immigration Act”, The London Economic, 19/04/2018:

[3] Decca Aitkenhead, “Sarah Teather: ‘I’m angry there are no alternative voices on immigration’.”, The Guardian, 12 July 2013.

[4] Andrew Grice, “Ed Miliband attempts to take on Ukip – with toughened immigration policies”, The Guardian, 24 October 2014: Ed Miliband attempts to take on Ukip – with toughened immigration policies | The Independent | The Independent

[5] Adina Campbell, “Payments for Windrush victims denied compensation”, BBC News, 5 September 2024: Payments for Windrush victims denied Home Office compensation – BBC News

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ashith Nagesh & André Rhoden-Paul, “Home Office unlawfully axed Windrush measures”, BBC News, 19 June 2024: Windrush Scandal: Home office unlawfully axed recommendations, court rules – BBC News

[8] Jim Dunton, “Home Office publishes internal ‘roots of Windrush’ report after FoI battle”, Civil Service World, 27 September 2024: Home Office publishes internal ‘roots of Windrush’ report after FoI battle

[9] Ibid.

Hostile Environment: the Windrush Scandal I

****************************

Dedication

To Nurse Thelma Rock, her mother, and her son Colin, who were our neighbours in the 1950s. Thelma’s mother slept at our house until she found a place of her own.

They were part of the Windrush generation

*****************************

Introduction

The creation of a “hostile environment” for migrants was announced by Theresa May, the UK’s Conservative (Tory) Home Secretary, in 2012. Although she said it was intended for “illegal” migrants, it turned out that, under this policy, almost anyone could be made “illegal” if they were either a migrant themselves or a descendant of one. This became clear as the Windrush scandal unfolded.

“Windrush scandal” is the name eventually given to the UK government’s cruel and unjust treatment of thousands of British citizens, notably in – though not confined to – the decade following 2012. The citizens in question were members of the “Windrush generation”, who had come perfectly legally from British colonies and ex-colonies in the Caribbean, to work in the UK, helping to rebuild the country after the Second World War. The first group came by boat, the SS Empire Windrush, in 1948. The scandal affected the original arrivals and their descendants, as well as subsequent arrivals and their descendants. Under Theresa May’s new legislation, they were told they were not British after all. They were sacked from their jobs and deprived of their citizenship rights. The policy was set up to fulfil the election promise of Prime Minister David Cameron in 2010 that he would reduce immigration to “less than tens of thousands” a year. In her turn, May undertook to ensure the removal of “illegal” migrants from the country. Some of the Windrush generation were indeed deported.

In this series of blogs, I will tell how the hostile environment was set up and how it was used against the Windrush generation, highlighting the case of one of its victims, Hubert Howard, to show in personal terms the devastating impact of the scandal on individuals. I will examine the response of the government after the scandal was revealed in 2017.

I will argue that what happened was not simply an accident. or the result of bureaucratic mismanagement, or due to poor judgment on the part of politicians and officials; it was the result of deliberate acts of government, having at their root the history of UK and European racism. I will show (contrary to the myth that post-war governments encouraged and welcomed these post-war immigrants) that, from the start, Labour and Conservative governments actively sought, by administrative means, to discourage and prevent them from coming to Britain. Later, they alleged that such immigration was harmful to British society in various ways. The allegations were proved embarrassingly groundless. These attempts continued throughout and beyond the 1950s, until parliament was finally provided with an excuse to pass the restrictive Commonwealth Immigration Act 1962.

I will show that in subsequent years the Conservative Party remained against large-scale immigration of black people into the UK and imposed strict legislative controls on them; I will also show that the Labour Party, though disguising its own hostility, introduced similar restrictive legislation. I will discuss the Labour Party’s approach to immigration and highlight events during the governments of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown between 1997 and 2010 suggesting that the hostile environment existed under Labour well before Theresa May’s announcement in 2012.

I will examine the failed compensation scheme set up by the Tory government and, finally, I will show that Windrush victims are still being targeted today, under a Labour government claiming to be committed to change.

But I begin with the announcement of the hostile environment policy and show how the Windrush scandal followed and how it became a catastrophe for so many people.

Creating hostility

During the UK general election campaign in 2010, David Cameron, leader of the Tory opposition, pledged to reduce the UK’s net immigration per year to “less than tens of thousands” if he became Prime Minister. After the election, he led a coalition government with the Liberal Democrats (LibDems). He appointed Tory MP Theresa May as Home Secretary, who seemed as determined as he was to get immigration numbers down. She announced her intention in an interview in The Telegraph in 2012, saying,“The aim is to create, here in Britain, a really hostile environment for illegal immigrants.”[1] The following year she introduced an Immigration Bill, which would become law in 2014, and explained its purpose in the following way:

Most people will say it can’t be fair for people who have no right to be here in the UK to continue to exist as everybody else does with bank accounts, with driving licences and with access to rented accommodation. We are going to be changing that because we don’t think that is fair … What we don’t want is a situation where people think that they can come here and overstay because they’re able to access everything they need.[2]

She was careful to say that her hostility was directed at people who were “illegal” and thus to imply that the hostility was “fair”. But we will see how easy it was for her to pin the “illegal” label on innocent people, make false accusations against them and turn their lives upside down.

At this stage, May’s legislation and her language could be seen as simply in line with a long-standing Tory approach to immigration. Her comments were reminiscent of remarks by a previous Home Secretary, referring specifically to asylum seekers: in 1995 Michael Howard had declared that the UK was seen as

a very attractive destination because of the ease with which people can get access to jobs and to benefits. And while, for instance, the number of asylum seekers for the rest of Europe are [sic] falling the number in this country are [sic] increasing [and] only a tiny proportion of them are genuine refugees.[3]

Likewise, Tory Social Security Secretary Peter Lilley told the Tory Party Conference in the same year:

Genuine political refugees are few. The trouble is our system almost invites people to claim asylum to gain British benefits. That can’t be right – and I’m going to stop it. Britain should be a safe haven, not a soft touch.[4]

In 2013, however, May made clear that the environment would now become unmistakably hostile. The hostility would be expressed not only in legislation but also in government actions. This included a crude attempt to frighten migrants into leaving the country and to create hostility to them in local communities: in July 2013, the Home Office sent vans, displaying the message, “In the UK illegally? Go home or face arrest”, into six London boroughs. It was a pilot scheme, lasting one month, and the Home Office claimed that it resulted in 60 people “voluntarily” returning to their home countries and that it saved taxpayers’ money.[5] There was, however, a good deal of public disquiet and the vans were not used again.

But the legislation, too, was unmistakably hostile. As May’s Immigration Bill started its journey through parliament, it was obvious that many of its provisions would be particularly worrying for asylum seekers: grounds of appeal against refusal and deportation would be reduced from 17 to four and a “deport first, appeal later” policy would be introduced for people judged as being at no risk of “serious irreversible harm” if returned to their countries of origin, or indeed to other countries similarly approved by the government.[6] This was particularly dangerous since such judgments, made by caseworkers or secretaries of state, are notoriously unreliable.[7] So these legal changes were worrying enough. But it became clear that Home Office definitions of who was an “illegal immigrant” were equally unreliable, and dangerous, as the Windrush scandal unfolded.

What happened to the Windrush generation under the hostile environment policy was particularly scandalous because this whole cohort of people who had been citizens for decades were suddenly told they were not citizens at all. The House of Commons Home Affairs Select Committee, which investigated the scandal, summed up what happened to them in a few succinct sentences. Members of the Windrush generation were

denied access to employment, healthcare, housing and other services in the UK. In some cases, people who had every right to live in the UK were targeted for removal, held in immigration detention, deported or prevented from returning to the UK from visits abroad. Upon trying to resolve their status with the Home Office, they faced obstacles such as “often insurmountable” requirements for decades-worth of evidence to demonstrate their time in the UK and significant application fees.[8]

When it came to removal from the country, some decided, with their history erased, to leave before they could be forcibly removed and thus retain some dignity.[9] For others, the hostile environment ruined their health.

Persecution enforced by law

May’s Bill passed into law, becoming the Immigration Act 2014. It required employers to demand evidence of their employees’ immigration and citizenship status, NHS staff to demand the same of their patients, private landlords of their tenants and banks of their customers. Other public bodies were instructed to do likewise, and new powers were given to check the immigration status of driving licence applicants, refusing those who could not provide evidence and revoking licences already granted.[10] When such checks were made, it turned out that large numbers of people who had lived and worked in the country for decades had no documents to prove their citizenship (no passports, no naturalisation papers). They were declared “illegal”. Most of them were part of the Windrush generation and their descendants.

Rhetoric versus reality

When the Empire Windrush passengers arrived at the UK’s border, no questions were raised about their citizenship or their right to enter and live in the UK. Indeed, for more than a century citizens of the British Empire had enjoyed those rights. In their rhetoric, many UK politicians treated this as a principle to be proud of. In 1954 Henry Hopkinson, Tory Minister of State for Colonial Affairs, declared:

We still take pride in the fact that a man can say civis Britannicus sum [I am a British citizen] whatever his colour may be and we take pride in the fact that he wants to and can come to the mother country.[11]

Moreover, rhetoric apart, the decision to maintain these long-standing rights after the war was taken on hard political and economic grounds: as the countries that had formed the British Empire began to gain their independence, and the Empire became the Commonwealth, good relations with those countries were deemed vital if Britain was to maintain an economic foothold in the regions of the world it once ruled. So, in the very year the Empire Windrush sailed, the British Nationality Act 1948 confirmed those rights to British citizenship.[12] Later, the Immigration Act 1971 confirmed them yet again: although the Act granted only temporary residence to most new arrivals, crucially it still granted Commonwealth citizens protection from deportation.[13] However, by the beginning of the next decade, an erosion of their right to protection had begun. The British Nationality Act 1981 created a new status – that of “British citizen”. In doing so, in the words of Lord Justice Underhill in the Court of Appeal in 2019, it

assimilated the position of Commonwealth citizens to that of other foreign nationals, by requiring them to naturalise … in order to acquire British citizenship.[14]

Arguably, the protection given by the 1971 Act still existed, since it had not been repealed. But by the end of the decade the Immigration Act 1988 had removed it. Section 1(5) of the 1971 Act had ensured that Commonwealth citizens “settled in the United Kingdom at the coming into force of this Act” would retain their freedom “to come into and go from the United Kingdom”.[15] The 1988 Act, however, removed it in a single sentence: “Section 1(5) of the … Immigration Act 1971 … is hereby repealed.”[16] During the passage of the 1988 Act through parliament, concerns had been raised in the House of Lords by Lord Pitt.[17] “I wish that the Government would think through these matters,” he said:

We are talking about people who have been here for 15 years. During those 15 years they have been contributing to the state through taxes, rates, their work and their contributions to society. In 1971 the Government gave them a pledge. I ask them for Christ’s sake to keep it.[18]

Despite this urgent plea, the Bill received the Royal Assent and became the Immigration Act 1988, and the protection given in the 1971 Act was removed. Nevertheless, the confirmation of their rights in the 1948 Act remained and another Act, Labour’s Immigration and Asylum Act 1999, seemed to give similar protection.

“… a great deal of thought …”

Theresa May claimed in the House of Commons in 2014 that the government had “given a great deal of thought to the way in which our measures will operate.”[19] May and her officials certainly noticed a provision in the 1999 Act. It worried them – and they did something about it. The Guardian reported in 2018:

All longstanding Commonwealth residents were protected from enforced removal by a specific exemption in the 1999 Immigration and Asylum Act – a clause removed in the updated 2014 legislation.[20]

They removed it deliberately, without warning and without debate.[21] One attempted justification, once the removal of the clause had been discovered, didn’t wash at all: a later Home Secretary, Amber Rudd, told the House of Commons in 2018 that the clause had been removed because it was unnecessary – there was already protection in the 1971 Act.[22] It didn’t wash, first, because the 1971 protection had been repealed, as we have seen, by the Immigration Act 1988; secondly, if they believed at the time that the protection still existed, why did they inflict the threats and punishments that immediately followed the passing of the 2014 Act? The answer is that they were determined to implement the hostile environment and, after giving the matter a great deal of thought, they removed the protection in the 1999 Act and set about persecuting the Windrush generation.

The consequences were predictable and intended. As employers, NHS staff, landlords, bank staff and other authorities checked the status of their current and potential workers, patients, customers and clients, more and more people were told that their lack of documentary proof of citizenship meant that they were not citizens at all. They were illegal. They had, in the words of Theresa May, “no right to be here”. They had to go. In April 2018, journalist Gary Younge gave examples of the cruelty inflicted on the Windrush generation and their descendants in the name of the “hostile environment”:

There’s Renford McIntyre, 64, who came to Britain from Jamaica when he was 14 to join his mum, worked as a tool setter, and is now homeless and unemployed, after he was fired when he couldn’t produce papers to prove his citizenship. Or 61-year-old Paulette Wilson who used to cook for MPs in the House of Commons. She was put in Yarl’s Wood removal centre and then taken to Heathrow for deportation, before a last-minute reprieve prevented her from being sent to Jamaica, which she last visited when she was 10 and where she has no surviving relatives. Or Albert Thompson, a 63-year-old who came from Jamaica as a teenager and has lived in London for 44 years. He was evicted from his council house and has now been denied NHS treatment for his cancer unless he can stump up £54,000, all because they question his immigration status.[23]

In the next blog, I will tell the story of Hubert Howard, one of the saddest victims of the hostile environment and the Windrush scandal.

[1] James Kirkup, “Theresa May interview: ‘We’re going to give illegal migrants a really hostile reception’”, The Telegraph, 25 May 2012: Theresa May interview: ‘We’re going to give illegal migrants a really hostile reception’ (telegraph.co.uk)

[2] Cited The Guardian, 10 October 2013: Immigration bill: Theresa May defends plans to create ‘hostile environment’ | Theresa May | The Guardian (accessed 28/5/2023).

[3] Playing the Race Card, 7 November 1999, Channel Four Television, London.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Operation Vaken: evaluation report, Home Office and Immigration Enforcement, 31 October 2013: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/operation-vaken-evaluation-report; Hattenstone, S., “Why was the scheme behind May’s ‘Go Home’ vans called Operation Vaken?”, The Guardian, 26 April 2018: Why was the scheme behind May’s ‘Go Home’ vans called Operation Vaken? | Simon Hattenstone | The Guardian

[6] Immigration Act 2014, s. 17(3), insertion 94B(3).

[7] Mouncer, Bob (2009), Dealt with on their Merits: the Treatment of Asylum Seekers in the UK and France, University of Hull, paras 6.5.9, 6.5.12, 6.6.1-6.6.4: file:///C:/Users/Bob/AppData/Local/Temp/b76ecf82-0f04-4115-975d-917a3a324502_Dealt%20with%20on%20their%20merits.zip.502/519233.pdf; Shaw, J. & Witkin, R. (2004), Get it Right: How Home Office Decision Making Fails Refugees, Amnesty International, London.

[8] The Windrush Compensation Scheme, House of Commons Home Affairs Committee Report (24 November 2021), para. 1: The Windrush Compensation Scheme – Home Affairs Committee (parliament.uk)

[9] “What is Windrush and who are the Windrush generation?”, BBC News 27 July 2023: What is Windrush and who are the Windrush generation? – BBC News

[10] Immigration Act 2014.

[11] Cited, Hayter, T. (2000), Open Borders: The Case against Immigration Controls, Pluto Press, London, p. 44.

[12] Ibid., p. 43.

[13] Immigration Act 1971, ss. 1(5) and 7 (1); Gentleman, A., “‘I’ve been here for 50 years’: the scandal of the former Commonwealth citizens threatened with deportation’”, The Guardian, 21 February 2018: ‘I’ve been here for 50 years’: the scandal of the former Commonwealth citizens threatened with deportation | Immigration and asylum | The Guardian

[14] Case No: CA-2021-000601, Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL (27/7/2022), para. 11: Microsoft Word – Howard for hand-down _2_.docx (dpglaw.co.uk)

[15] Immigration Act 1971, s.1(5): “The rules [made by the Secretary of State relating to how the Act would work in practice] shall be so framed that Commonwealth citizens settled in the United Kingdom at the coming into force of this Act and their wives and children are not, by virtue of anything in the rules, any less free to come into and go from the United Kingdom than if this Act had not been passed.”

[16] Immigration Act 1988, s,1: Immigration Act 1988 (legislation.gov.uk)

[17] David Pitt was born on the Caribbean island of Grenada in 1913. He won the Island Scholarship to have further education abroad and studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh. He returned to the Caribbean, but settled in Britain in 1947. He was given a life peerage in 1975. He died in 1994.

[18] Cited, Williams, W. op. cit., p. 58: 6.5577_HO_Windrush_Lessons Learned Review (publishing.service.gov.uk).

[19] Hansard, House of Commons, 30 January 2014, cols 1124-25: Immigration Bill – Hansard – UK Parliament

[20] Taylor, D., ”UK removed legal protection for Windrush immigrants in 2014”, UK removed legal protection for Windrush immigrants in 2014 | Commonwealth immigration | The Guardian

[21] Ibid.

[22] Hansard, House of Commons, 23 April 2018, cols. 628-29).

[23] Younge, G., “Hounding Commonwealth citizens is no accident. It’s cruelty by design”, The Guardian, 13 April 2018: Hounding Commonwealth citizens is no accident. It’s cruelty by design | Gary Younge | The Guardian

No change from Labour, whatever the Observer says

The Observer article below welcomes Labour leader Keir Starmer’s statement on Labour’s approach to small boats, people smugglers, deportations and refugee policy generally. In contrast to the left’s view that there is little to “differentiate a possible future Labour government from the present Conservative one”, it claims to detect “a sharp dividing line between the government and Labour on asylum policy.” It says Labour is offering a humane, pragmatic and commonsense approach in contrast to the Tories’ populism and its “cruel, unworkable policy”.

The paper is right to say that the government has removed the right of all migrants who have arrived in small boats to claim asylum, when most of them would qualify for refugee status if they did; it is right to deplore the measures the government have introduced “to detain them until they can be deported to another country for their claim to be processed”; in the light of the government’s keenness to deport asylum seekers it deems to be “illegal”, the article is right to point out that no deportation deals have been achieved with any country except Rwanda (and the Supreme Court has yet to rule on the legality of that deal); it is also right to criticise the backlog the government has allowed to develop in the processing of asylum claims, so that “83% of claims made in 2018 had not been processed five years later”. The article is right to condemn the Tory policy package.

But the Observer is wrong to say that the “real difference” between Labour and the Tories is that Labour “would scrap the government’s unworkable and cruel detention and deportation policies, restoring the right of people to claim asylum in the UK.” It will do this, the Observer seems to believe, by investing in “1,000 extra case workers and a returns unit of 1,000 staff to process claims much more quickly and deport those whose claims are rejected.” This would work because Labour would come to a deal with the European Union (EU) “in which the UK would accept a quota of refugees in exchange for being able to return those who cross the Channel in small boats.” But even if such a deal could be reached, we would still be left, under Labour, with the same old “detention and deportation” policy. None of the refugees in small boats will have their claims considered here. If the Observer thinks that shunting vulnerable and desperate people around Europe as they wait for decisions on their future is what it calls “a far better approach”, so be it. The refugees may not agree. Moreover, in the same article, the Observer admits that “pan-European cooperation has never worked well in the bloc and has broken down further in recent years.” The Observer must know it’s clutching at straws.

But there is one thing Starmer has to do before we can believe in this tale of “differentiation” between Labour and the Tories on asylum. He has to commit the Labour Party to repealing the Illegal Migration Act 2022. While the Act remains, Tory policy remains unchanged. Unless it is repealed, there can be no “differentiation” between the parties. In its guidance to the Act, the government makes clear that

anyone arriving illegally in the United Kingdom will not have their asylum claim, human rights claim or modern slavery referral considered while they are in the UK, but they will instead be promptly removed either to their home country or to a safe third country to have their protection claims processed there. (https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2023/37/notes/division/3/index.htm)

Obviously the Act must be repealed. But both Starmer and shadow immigration minister Stephen Kinnock have refused to commit to repealing it. While it stands, so does the policy.

The article begins by setting the “Observer view” in the context of Starmer’s political approach as a whole. Keir Starmer, it says,

has made clear that under his leadership a first-term Labour government would stick to tough fiscal rules, and has ruled out making any unfunded spending commitments in the run-up to the next election. That has fuelled criticism from some on the left of his party, who argue that this has limited the extent to which he has been able to differentiate a possible future Labour government from the present Conservative one.

It says Starmer’s asylum policy makes Labour different. It doesn’t.

What that means for our voting intentions next year is up to us all. But it puts a very big strain on mine.

No repeal, no vote

I’ve just noticed that this year marks a kind of grim anniversary, one that we might want to forget. Just a decade ago, in 2013, Home Secretary Theresa May devised what would become the Immigration Act 2014 and explained its purpose in the following way:

“Most people will say it can’t be fair for people who have no right to be here in the UK to continue to exist as everybody else does with bank accounts, with driving licences and with access to rented accommodation. We are going to be changing that because we don’t think that is fair.”

She wanted to “create a really hostile environment” for illegal migrants: “What we don’t want”, she said, “is a situation where people think that they can come here and overstay because they’re able to access everything they need.”

The Act reduced migrants’ rights, including rights of appeal against deportation. It introduced a “deport first, appeal later” policy for people regarded as being at “no risk of serious irreversible harm” if returned to their country of origin: such judgments, made by caseworkers or Secretaries of State, are notoriously unreliable and dangerous. May’s legislation and her language were in line with a long-standing and nasty Tory approach to asylum and immigration. Her comments were reminiscent of a previous Home Secretary’s remarks, which referred specifically to asylum seekers: in 1995 Michael Howard had declared that the UK was seen as

“a very attractive destination because of the ease with which people can get access to jobs and to benefits. And while, for instance, the number of asylum seekers for the rest of Europe are falling the number in this country are increasing [and] only a tiny proportion of them are genuine refugees.”

Likewise, Social Security Secretary Peter Lilley told the Tory Party Conference in the same year:

“Genuine political refugees are few. The trouble is our system almost invites people to claim asylum to gain British benefits. That can’t be right – and I’m going to stop it. Britain should be a safe haven, not a soft touch.”

The hostile environment led to the Windrush scandal, in which long-standing UK citizens were told they had no such status and were deported to countries they knew nothing about. Some died as a result of the treatment they received at the hands of the woman who now, bizarrely, claims to defend the rights of smuggled children against the provisions of the latest two bits of Tory legislation to abuse, detain and deport some of the most vulnerable and desperate people in the world.

The new laws that have now been brought in by the Sunak government (the Nationality & Borders Act and the Illegal Immigration Act) are harsher and more cruel than anything even Theresa May dreamt of. The rhetoric that goes with them is nastier and more dangerous. We need to find ways of supporting victims of these policies. And the least we can do is put pressure on Labour MPs and, later, candidates in the 2024 general election, to promise to repeal the Tory Acts if Labour wins the election. Tell them: No repeal, no vote.

Like

Comment

Share

Abstaining is not an option – Labour must reject Patel’s Bill

I’ve written to Labour’s Shadow Home Secretary, Nick Thomas-Symonds, and my local MP, Emma Hardy, asking them to make sure that Labour votes against Priti Patel’s new asylum Bill.

Scrutiny of the Nationality and Borders Bill begins tomorrow (19 July). It is of particular interest to me because of my earlier research at Hull University on the treatment of asylum seekers. My particular concern today is that Labour should give no credibility to the Bill. In particular Labour shouldn’t abstain at any point on the grounds that “we understand voters’ concerns”. Labour did this on the Welfare Bill in 2015 and the front bench tried to do it on the Immigration and Social Security Bill in, I think, 2017. But it is time to stand up for a few principles now and not just run scared. The current Bill is the worst Bill of its kind that I can remember and it will do untold harm to people from the moment it becomes law. Labour should have no truck with it from day 1.

I’ve looked at the Bill itself now, so I thought I’d make some preliminary comments. I will focus on Part 2, which is about asylum, but for now I will only mention a couple of points.

Section 10 is unacceptable from the outset: it immediately creates two groups of refugees. Group 1 refugees are legal; Group 2 refugees are not. They are “unlawful”. What makes them unlawful is, according to s.10 (4), because “a person’s entry into or presence in the United Kingdom is unlawful if they require leave to enter or remain and do not have it.” This new definition of “unlawful” makes the vast majority of asylum seekers illegal. The Bill achieves this end, in part, because it creates an entirely new offence. According to s.37(2), (C1), a person who

“(a) requires entry clearance under the immigration rules, and

(b) knowingly arrives in the United Kingdom without a valid entry

clearance,

commits an offence.”

Plus, according to s. 37 (3):

“In proceedings for an offence under subsection (C1) above of

arriving in the United Kingdom without a valid entry

clearance … (b) proof that a person had a valid entry clearance is to lie on the defence.”

This offence of “arriving in the UK” is a new offence, created by this Bill. According to criminal defence barrister Aneurin Brewer, the current situation is that

“those who merely arrive, immediately claim asylum and are as a result admitted to the UK while their asylum claim is processed have not entered the UK illegally.” https://www.freemovement.org.uk/prosecutions-for-assisting-unlawful-immigration-in-small-boats-cases-the-key-to-acquittal/

If this Bill is passed, they will have done so and thus, although the Bill doesn’t breach Convention Article 31 (1) according to Patel’s narrow and restrictive interpretation, it certainly ignores the spirit of UNHCR recommendations on applying a “flexible and liberal” approach and on giving “the benefit of the doubt”.

Patel is legally entitled to do this. It may be worth bearing in mind that the Refugee Convention is not a perfect instrument for protecting refugees. Its final form was the result of a deal. Every state wanted to limit its obligations to give protection to refugees. So the Convention and UNHCR’s Guidelines, despite talk of liberality and benefit of doubt, provided them with caveats and ways of avoiding their responsibilities. One example of this is Article 31(1). While it is generally interpreted as prohibiting governments from imposing any penalties on asylum seekers who arrive without passports or other travel documents, governments generally do impose penalties because the article talks of asylum seekers who come “directly” from the country of their persecution and refers to illegal entry. The word “directly” can be interpreted to mean that penalties can be imposed if the asylum seeker comes to the UK and passes through another “safe” country where, it is always assumed, they could have claimed asylum. This interpretation of the word “directly” was probably the reason why the Dublin Convention, now not applicable after Brexit, was not regarded as a contravention of the Refugee Convention. one of the things Patel is proud of doing in this Bill is making this requirement part of UK law now, thus dealing with the “problem” of the disappearance of the Dublin Convention after Brexit.

So what I’m saying is that, in principle, the Convention seems to establish the primacy of refugee protection, but in its detail and in practice it has proved to be ambiguous and open to a variety of interpretations. UNHCR “advocates that governments adopt a rapid, flexible and liberal process” when dealing with asylum applicants because it recognises “how difficult it often is to document persecution”. However, its interpretation of the Convention contradicts this stance. In its definition of a refugee, the Convention’s reference to persecution “for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion” suggests the possibility of group persecution and a collective refugee experience. But, when interpreted by UNHCR, the definition turns out to be based on a concept of persecution in which the burden of proof falls on the individual asylum seeker. Thus people “who apply for refugee status normally need to establish individually that their fear of persecution is well-founded”, i.e. they must provide evidence that it is not just their social group, members of their political party or people who share their religion or ethnicity who are in danger but themselves as individuals. I have sat in a good few solicitors’ offices listening to them explaining to their clients how their letters, newspaper reports, and their photographs are absolutely not proof. A “flexible and liberal process” becomes less likely as governments demand this rigorous standard of proof. To put the burden of proof on refugees is to consider them guilty until proved innocent.

But Patel is clearly entitled to do what she’s trying to do here. She can invent laws and move the goalposts, she can choose only to follow the UNHCR advice that suits her and ignore the rest. But I think Labour should do its best to stop her. It should, if it can’t eliminate all her hostile purposes from the Bill, vote against the whole shebang and campaign loudly against it from the start. It should never abstain. Not just because of the Refugee Convention, important though that is. But because of the principle of refugee protection and the defence of human rights.

Labour’s plan for jobs

Just a few random thoughts on Labour’s plan for jobs (see link below). It begins with this statement:

The Government was too slow into lockdown, too slow on testing and too slow to protect jobs. Now, the Chancellor’s one-size-fits-all withdrawal of furlough risks creating a jobs squeeze that will put people’s livelihoods at risk.

Absolutely right. And on lockdown, many Tories knew that it was being imposed later than it should have been. Ken Clarke had well-informed friends who told him, two weeks before it began, that he should lock down now. He did.

However, Labour failed to oppose the early lifting of the lockdown, in fact it explicitly supported it. Arguably, it is because of that early lifting that the government is having to impose local lockdowns and targeted quarantines now, with a policy of lifting here and locking down there, at short notice and with more than a hint of chaos.

Still, having got that out of the way, the first point of Labour’s plan is:

-

Fight for jobs:

fix the furlough scheme to support people in the worst-hit industries.

For sure, “fix the furlough scheme” is one of the things we should now demand. But this is too vague. The demand should be to “fix the furlough scheme” by making it compulsory on all employers who want to lay off workers who can’t work from home and by keeping it in place until a vaccine is produced and being used successfully. This will cost money. But Labour must have the courage to spell out a strategy that costs more. If it doesn’t, it will quickly become an extension of the Tory party. I know Starmer doesn’t want to “make unreasonable demands”, but this isn’t unreasonable. We’re in a crisis the like of which we haven’t seen before.

-

Back our businesses:

with a £1.7 billion fightback fund to stop firms going under and save our high streets.

This is good – except that there’s no detail and £1.7bn doesn’t seem enough, considering the government’s past failures have put us into a longer crisis than might have been necessary. Again, spell out a strategy that costs more.

-

“Leave no-one behind:

with targeted support for areas forced back into lockdown.”

This is good, and will be supported by most people. No detail though.

-

Keep workers safe:

by protecting workers’ rights, by boosting sick pay, making workplaces safe, and giving our NHS and care services the resources to stop a second wave.

Absolutely. But, again, there’s no detail. In particular, workers’ rights are absent in many workplaces. They need to be given in the first place and then protected. The way to do that is to campaign for union membership everywhere and make union recognition mandatory in all workplaces. When I worked in France at the fag-end of the UK’s Thatcher period I was amazed to discover that no employer in France could refuse to negotiate with a union rep. Attacks on workers’ rights have taken place in France under Macron and I’m not sure of the current state of play. But everything is possible, whether there or here, and we should demand everything. By the way, looking at Point 2 above, they’re not remotely beginning to be “our” businesses unless the measures suggested here are in place. Saying that they are is a Labour version of Cameron’s “we’re all in this together”. We weren’t then, and they’re not “our” businesses now.

-

“Drive job creation:

by investing in infrastructure, speeding up progress to zero-carbon economy and improving access to skills and training.”

All this is good. What its value as a promise may be, I don’t know: on speeding up progress to a zero-carbon economy, Starmer has shelved Labour’s previous target of 2030. Let’s wait and see, he says. Wasn’t that Stanley Baldwin’s motto?

Limited enforcement

Labour has a plan “to ease the 14-day quarantine measures” (Labour List, 8/6/2020). The proposal for “a testing procedure for travellers, with results provided within 48 hours” is a good one – as long as people are quarantined for that 48 hours in a specified space. But if the government rejects that proposal, Labour must on no account sympathise with the poor travellers holed up for 14 days. Because they won’t be. According to The Guardian, they will be able to go food shopping, change accommodation and use public transport from airports. Only one-fifth of them will be spot-checked to see if they are staying at their notified address. Enforcement of the quarantine will be limited (The Guardian, 1/6/2020).

So where’s the quarantine? There is no quarantine worth the name. Instead, there is a smoke-and-mirrors operation to fool us that there is. That’s because the travellers are likely to be business. Or tourists, which is the same thing. And opening up business is important. More important than health.

Let’s break these promises

Labour’s 2017 manifesto promised an end to free movement and that, instead of the Tories’ £30,000 salary threshold that migrants need to be earning before they dare to take even one step on to our territory, a Labour government would ensure that migrants would have “no access to public funds”. These are promises that should be broken. Like many Labour Party members I’m in favour of free movement, both for me and for others. And as for the second promise, here’s an example of what “no access to public funds” means in practice, It’s taken from Mike Cole’s book “Racism”:

As a direct result of the 2007–08 financial crisis … increasing numbers of people in Peterborough were forced to become homeless, and resorted to squatting in back yards or setting up desperate makeshift camps, which were reminiscent of shanty towns, on roundabouts and in woods. By 2010 it was estimated that as many as 15 camps were scattered around the city. In the same year, a project that was the first of its kind in the country was launched in Peterborough. It involved rounding up homeless migrants and attempting to force them to leave the United Kingdom. The then immigration minister Phil Woolas stated: “People have to be working, studying or self-sufficient and if they are not we expect them to return home …. This scheme to remove European nationals who aren’t employed is getting them off the streets and back to their own country.” Stewart Jackson, a local Conservative MP, described them as “vagrants” and remarked: “I don’t know how these migrants are surviving sleeping rough on roundabouts and bushes but they are a drain on my constituents and taxpayers …. If they are not going to contribute to this country, then, as citizens of their home country, they should return there.”

Typical Tory language? Yes, but Phil Woolas was a Labour minister and MP for Oldham East. Labour must take “no access to public funds” out of its plans for the next manifesto, out of its lexicon of policies and out of its collective head—except as a no-go area.