“God bless us, everyone” — or kind of …

First, an interesting and welcome headline in The Guardian:

“C of E to challenge Tommy Robinson’s ‘put Christ back into Christmas’ message”

The C of E is, of course, the Church of England. The state church, whose bishops sit in the House of Lords. King Charles II is the Church’s head.

There will be a poster campaign:

The posters, which will go on display at bus stops, say “Christ has always been in Christmas” and “Outsiders welcome”. They will also be available for local churches to download and display over the festive period.

The Guardian continues:

“The C of E’s decision to challenge Robinson’s extreme rightwing stance comes amid growing unease among church leaders about the rise of Christian nationalism and the appropriation of Christian symbols to bolster the views of his supporters.”

Not a moment too soon. If Farage becomes prime minister in 2029, the C of E will have little room to manoeuvre and will have to speak and do as it’s told, on pain of disestablishment. It’d be a pity for it to lose all that pomp and privilege. Let’s hope the latest move is not too late.

I see some of the other churches are joining in:

“The Joint Public Issues Team, a partnership between the Baptist Union of Great Britain, the Methodist church and the United Reformed church is offering a ‘rapid response resource’ for local churches trying to ‘navigate the complexities’ of Christian nationalism and the ‘co-option of Christian language and symbols – including Christmas – for a nationalist agenda’.”

Of course, the C of E is itself an expression of “Christian nationalism”, what with the king being its head and all that. Now there’s a complexity to navigate if ever there was one. At least the others, all those Baptists, United Reformists, Methodists and random Pentecostals, don’t have that hanging round their necks. And I wish them luck (even the C of E). I’m on their side.

Amen, in fact.

Progressively taking soundings

The Guardian this morning says:

“Keir Starmer to launch progressive fightback against ‘decline and division’ fuelled by far right”

I can see the OED having to reassess its definition of the word “progressive” soon. More work for them — they’re already busy modifying “change”.

Anyway,

“Senior sources said Starmer had begun to spend significantly more time taking soundings from MPs … As well as spending time last week in the voting lobbies and tea rooms with MPs, Starmer hosted a delegation for breakfast in No 10 on Monday morning.”

I get why he would go to the tea rooms — taking soundings is thirsty work. And there’s no substitute for a traditional (English) breakfast to get you off on the right foot. But the lobbies? I thought you just went there to vote. Unless this is a bullying operation: “No, Richard, you’re in the wrong lobby. You want the progressive lobby.” It’ll get Keir nowhere though. Richard Burgon, the honourable member for Leeds East, knows the meaning of “honourable ”.

More work for the OED, though. On the definition of “taking soundings”!

No change

So I woke up this morning, noting a slight chill in the air. But nothing spectacular, either weatherwise or any other wise. There certainly doesn’t seem to be any change in the political scene at all.

Yet there is a flurry of headlines that think the opposite, and the BBC spells it out clearly: “Sir Keir Starmer is expected to announce the UK’s recognition of a Palestinian state in a statement on Sunday afternoon.”

There are two main problems with this. One is that there is no Palestinian state waiting to be recognised. The other is that UK policy has long been to support a two-state solution. This would necessarily involve recognition. So, as of this slightly chilly “Sunday afternoon”, nothing will have changed. Yet we are to believe that brave Keir has looked at the situation over the last few weeks and, calling into play the courage for which he is justly famed, has “shifted” his policy in defiance of Trump. Bravo! But it’s all bullshit.

In any case, Netanyahu, backed by Trump, won’t be making way for a Palestinian state. There will be no Palestinians left in the West Bank or Gaza, when Bibi and Trump have done their worst; and let’s not forget that Gaza itself is set to be the new Riviera, set up for rich people who have become bored with Nice, Cannes and Monte Carlo, with their nice clean beaches. The new, Trump-owned beaches of Gaza won’t just be clean: they’ll have been cleansed.

What more could you want?

Labour, immigration and Enoch Powell

Introduction

In an earlier blog, we saw how working parties were set up after the Second World War whose task was to justify racist immigration controls.[1] They repeatedly failed to do so, but they continued their efforts for 17 years. Finally, employing a series of manifestly false arguments, the Tories passed the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962, complete with racist controls.

Hostility to black Commonwealth immigrants, however, was not confined to the Tories. It was, after all, the Labour government elected in 1945 that set up the working parties in the first place. Kieran Connell writes of “the relentless presence of racism in 1940s Britain, and the related influence of ideas about race.”[2] Labour was part of that pressure and influence. In 1946, Labour Home Secretary Chuter Ede told a cabinet committee that when it came to immigration he would be much happier if it “could be limited to entrants from the Western countries, whose traditions and social backgrounds were more nearly equal to our own.”[3] When the Empire Windrush arrived in 1948 with 492 Jamaicans ready to work to rebuild post-war Britain, 11 Labour MPs wrote to Prime Minister Clement Attlee, notifying him of “the fact that several hundred West Indians have arrived in this country trusting that our government will provide them with food, shelter and employment.” They feared that “their success might encourage other British subjects to follow their example.” This would turn Britain into

an open reception centre for immigration not selected in relation to health, education and training and above all regardless of whether assimilation was possible or not … An influx of coloured people domiciled here is likely to impair the harmony, strength and cohesion of our public and social life and cause discord and unhappiness among all concerned.[4]

Attlee replied to the letter, reassuring them that “if our policy [of unrestricted immigration] were to result in a great influx of undesirables we might, however unwillingly, have to consider modifying it.”[5] Kenan Malik notes that this exchange of letters contains many assumptions that shaped official and popular attitudes to post-war black immigration:

There are two kinds of British citizens: white people and “undesirables”. Britain is in danger of being swamped by immigrants taking advantage of the nation’s generosity. Immigrants’ standards of “health, education and training” are lower than those of British people. Black people are incapable of assimilating British culture. A large black presence in Britain would create social tensions.[6]

Such attitudes didn’t end with that decade but continued through the 17 years to 1962. At first, therefore, it seems puzzling that Labour opposed the 1962 Act throughout its passage through parliament. It did so, however, in the context of the ending of British rule in countries that were previously part of the British Empire and were now becoming independent nations. Britain’s post-war determination to justify immigration controls against black immigrants now came up against its need to build Commonwealth institutions and keep a political and economic foothold in the countries it once ruled. To that end, the Commonwealth was increasingly promoted as a “family of nations”. Any suggestion that the racism that had served British interests “out there” in the old Empire might now be applied to citizens of the new Commonwealth when they came here could threaten the whole project. This was a dilemma for both the main political parties. Lord Salisbury (Lord President of the Council and Tory Leader of the House of Lords) was a strong advocate of immigration controls. When a working party reported that there was no evidence that black immigrants were more inclined to criminality than white natives, he roundly declared in 1954: “It is not for me merely a question of whether criminal negroes should be allowed in … it is a question of whether great quantities of negroes, criminal or not, should be allowed to come.”[7] Lord Swinton (Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations) agreed but warned Salisbury of the dangers ahead: “If we legislate on immigration, though we can draft it in non-discriminatory terms, we cannot conceal the obvious fact that the object is to keep out coloured people.”[8] Other Tories were more cautious. Henry Hopkinson, Minister of State at the Colonial Office, declared: “We still take pride in the fact that a man can say civis Britannicus sum [I am a British citizen] whatever his colour may be and we take pride in the fact that he wants to and can come to the mother country.”[9] In 1958, Arthur Bottomley, on Labour’s front bench, had also spoken up for the new Commonwealth and against immigration controls:

The central principle on which our status in the Commonwealth is largely dependent is the “open door” to all Commonwealth citizens. If we believe in the importance of our great Commonwealth, we should do nothing in the slightest degree to undermine that principle.[10]

It seemed for a while as if the battle between racist immigration controls, espoused by both parties, and the Commonwealth ideal of a “family of nations”, also espoused by both parties, might be won by the Commonwealth. But when Labour won the 1964 general election, the new government immediately refocused on immigration controls and increased the restrictions in the 1962 Act. In the years to come, Labour would introduce legislation and rules to reduce black immigration whenever it got the chance.

Facing both ways

Labour in government dealt with the embarrassing contradiction between racism and the “Commonwealth ideal” by facing both ways and hoping nobody would notice. It constantly sought to reassure voters that it “understood” their “genuine concerns” about immigration and enacted increasingly restrictive immigration laws. At the same time, it denied being racist and passed legislation aimed at creating “good race relations”. What often emerged from this process, however, were weak race-relations laws, suggesting that the government’s priority was to curb immigration. Thus, the Race Relations Acts of 1965 and 1968 were half-hearted affairs. While the 1965 Act did prohibit “incitement to racial hatred”, when it came to discrimination it didn’t include discrimination in housing and employment, and it didn’t apply to the police; and while the 1968 Act went further and included discrimination in housing and employment, the government decided that this would not apply to the police, who had exerted strong pressure on the cabinet not to include them. Home Secretary James Callaghan told the cabinet at the time:

The opposition of the Police Federation to amending the [police disciplinary] code has been intense and deep-seated. And the Police Advisory Board has been unanimous in advising me not to proceed.[11]

In 1968, the government introduced a new Commonwealth Immigrants Act which seemed set to undo the limited good the two Race Relations Acts had done. The Act refused all Commonwealth immigrants entry into the UK unless they could prove they were – or one of their parents or grandparents was – born, naturalised or adopted in the UK, or unless they were otherwise registered in specified circumstances as UK citizens.[12] This meant that citizens in the “white” Commonwealth (Canada, Australia, New Zealand) were not refused entry. The Act was Labour’s response to the Kenyan Asians crisis, when racism on the far right of the Tory Party was at its most virulent and dangerous. It was a decision to follow the Tory racists.

The Kenyan Asians: race, nation and the end of Empire

The Kenyan Asians were being forced out of Kenya by its government’s Africanisation policy, which excluded Kenya’s Asian population from employment and other rights. Many of them had British passports, which a British Conservative government had allowed them to retain following Kenya’s independence in 1963. Now, not surprisingly, they expected to be able to use them. The Labour government, however, decided otherwise. 80,000 of them, out of a total of about 200,000, had arrived in Britain by early 1968 and the government had been under pressure from several directions to keep them out. A campaign against allowing them to enter the country was launched by Tory MPs Duncan Sandys and Enoch Powell. Sandys had already told the Conservative Party Conference in 1967:

We are determined to preserve the British character of Britain. We welcome other races, in reasonable numbers. But we have already admitted more than we can absorb.[13]

Now Powell set about raising the temperature: he used deliberately provocative and racist language. He claimed a woman had written to him (anonymously, Powell alleged, out of fear of reprisals if her identity became known) claiming abuse by “Negroes”. She had, according to Powell’s story, paid off her mortgage and had started to let some of the rooms in her house to tenants; but she wouldn’t let to “Negroes”:

Then the immigrants moved in [to the neighbourhood]. With growing fear, she saw one house after another taken over. The quiet street became a place of noise and confusion. Regretfully, her white tenants moved out … She finds excreta pushed through her letter box. When she goes to the shops, she is followed by children, charming, wide-grinning piccaninnies.”[14]

Powell declared:

Those whom the gods wish to destroy, they first make mad. We must be mad, literally mad, as a nation to be permitting the annual inflow of some 50,000 dependants, who are for the most part the material of the future growth of the immigrant-descended population. It is like watching a nation busily engaged in heaping up its own funeral pyre.[15]

The British Empire, which Powell had supported, was no more. Its former subjects had fought for, and won, their independence. Satnam Virdee argues that, for Powell,

Black and Asian workers had now become the unintended reminder of peoples abroad who wanted nothing to do with the British Empire. And, in the mind of Powell, this invited the question, “What are they doing here in Britain?”[16]

For Powell, they “represented the living embodiment of the Empire that now was lost, a painful and daily reminder of [Britain’s] defeat on the world stage.”[17] For that reason, as well as his nightmare that the “immigrant-descended population” would lead to a “funeral pyre”, he was in favour of their repatriation (or, as he put it, their “re-emigration”) to the countries they or their parents had come from:

I turn to re-emigration. If all immigration ended tomorrow, the rate of growth of the immigrant and immigrant-descended population would be substantially reduced, but the prospective size of this element in the population would still leave the basic character of the national danger unaffected.[18]

The way to solve this problem was through “the encouragement of re-emigration”. Powell noted that no such policy had been tried, so there was no evidence from which to judge potential success or failure: “Nobody knows,” he said. So he once again called his constituents in aid to support him:

I can only say that, even at present, immigrants in my own constituency from time to time come to me, asking if I can find them assistance to return home. If such a policy were adopted and pursued with the determination which the gravity of the alternative justifies, the resultant outflow could appreciably alter the prospects.[19]

The leader of the Tory opposition, Edward Heath, sacked Powell from the shadow cabinet after the speech. But there were demonstrations in support of Powell in the immediate aftermath of the speech and his sacking. There were strikes by thousands of workers. They began in the West Midlands, where Powell’s constituency was located. Construction workers and power workers struck in Wolverhampton and Birmingham, there were strikes in Coventry and Gateshead. Then they spread to the London docks and the meat porters of Smithfield market. Strikers marched “from the East End to Westminster carrying placards reading ‘Don’t knock Enoch’ and ‘Back Britain, not Black Britain’.”[20]

But Powell remained sacked. His intervention was not welcomed by mainstream politicians in the Tory party, Labour or the Liberal Party. For one thing, his provocative racism seemed likely to threaten Britain’s social stability if unchecked. Moreover, good relations with the independent countries of the Commonwealth were still deemed vital to British interests: Powell’s racism not only threatened stability at home, it endangered good and profitable relations abroad. Nevertheless, there were some in official circles who seemed to believe that government promises to its citizens could be broken with impunity. Eric Norris, the British High Commissioner in Nairobi, was against allowing the Kenyan Asians in and he watched them as they queued outside his office demanding that the British government keep its promises and honour its commitments: “They all had a touching faith”, he later said scornfully, “that we’d honour the passports that they’d got.”[21] There had been still other pressures on the government: the far-right National Front – whose preoccupations were, like Powell’s, with white British identity and the repatriation of black and Asian immigrants – were stirring in the same pot. But the government could have resisted these pressures. The liberal press, churches, students and others opposed the campaign against the Kenyan Asians and could have been called in aid. Instead, it joined the Tory racists. Home Secretary James Callaghan wrote a memo to the cabinet:

We must bear in mind that the problem is potentially much wider than East Africa. There are another one and a quarter million people not subject to our immigration control … At some future time we may be faced with an influx from Aden or Malaysia.[22]

The Act was passed in 72 hours. It met Callaghan’s wider fears, and it rendered the Kenyan Asians’ passports worthless. No wonder that a year later The Economist declared that Labour had “pinched the Tories’ white trousers”.[23]

[1] By Hook or by Crook – Determined to be Hostile: https://bobmouncer.blog/2025/05/04/__trashed-2/

[2] Connell, Kieran (2024), Multicultural Britain: A People’s History, C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd., London, p. 46.

[3] Cited, ibid., p. 20.

[4] Cited, Malik, Kenan (1996), The Meaning of Race: Race, History and Culture in Western Society, Macmillan, Basingstoke, p. 19.

[5] Cited, ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Carter, B., Harris, C. & Joshi, S. (1993), “The 1951-55 Conservative Government and the Racialization of Black Immigration”, in James, W. & Harris, C. (eds), Inside Babylon: the Caribbean Diaspora in Britain, Verso, London, p. 65.

[8] Spencer, I. (1997), British Immigration Policy since 1939: the Making of Multi-Racial Britain, Routledge, London, p. 64.

[9] Hayter, T. (2000), Open Borders: the Case against Immigration Controls, Pluto Press, London, p. 44.

[10] Foot, P. (1968), The Politics of Harold Wilson, Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, p. 251.

[11] “Callaghan: I was wrong on police and race”, BBC News, 8 January 1999: BBC NEWS | Special Report | 1999 | 01/99 | 1968 Secret History | Callaghan: I was wrong on police and race

[12] Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1968, s. 1 (2A).

[13] Playing the Race Card, 24 October 1999, Channel Four Television, London.

[14] Palash Ghosh, ”Enoch Powell’s ’Rivers of Blood‘ Speech”, International Business Times, 14/6/2011: Enoch Powell’s “Rivers of Blood” Speech (FULL-TEXT) | IBTimes

[15] Ibid.

[16] Virdee, S. & McGeever, B. (2023). Britain in Fragments: Why things are falling apart, Manchester University Press, Manchester, p. 71.

[17] Ghosh, op cit.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Virdee, S. & McGeever, B. (2023). Britain in Fragments: Why things are falling apart, Manchester University Press, Manchester, pp., 72-74.

[21] Playing the Race Card, 24 October 1999, Channel Four Television, London.

[22] Cited, Hayter, T. (2000), Open Borders: the case against immigration controls, Pluto Press, London, p. 53.

[23] Cited, ibid., p. 51.

By hook or by crook — determined to be hostile

Introduction

In recent blogs, I examined the hostile environment policy introduced by UK Home Secretary Theresa May during the early 2010s and the political scandals and human tragedies that followed: the Windrush and Mediterranean scandals.[1] Although at first sight the hostile environment policy seemed to be the creation of Conservative (Tory) governments, first under David Cameron and then under Theresa May, a closer examination raised questions about the policies on immigration and race adopted by all the main political parties over a much longer period. I will show, in particular, that both Tory and Labour governments have long been enthusiasts for racist immigration controls. I begin in 1945 and the need for reconstruction of the country after the destruction wreaked during the Second World War. In doing so, I will need to destroy a myth that has comforted most of us for many years. It is the myth that a universal welcome was given by governments of the UK and its people to the mainly Caribbean immigrants who came to help reconstruct the country after the war. The reality, however, was different and more complex. Acknowledging this reality will be essential if we are to understand the decades that followed.

Reconstruction

The task of reconstruction in the UK after the Second World War was massive and daunting: many workers had been killed in the fighting and much of the country’s infrastructure and industry had been destroyed in the bombing. Workers were certainly needed and the government tried, first, to persuade workers at home to relocate to different parts of the country where the need was greatest. This had limited success, as did the government’s attempts to recruit workers from the devastated European continent. There was, however, a third source of labour that could be tapped: for at least a century no official distinction had been made between citizens of the British Empire when it came to their right to enter and live in Britain. However, contrary to the myth still propagated and almost universally accepted today, the post-war Labour government was reluctant to use this source if it meant recruiting non-white people from the Caribbean, Africa and the Indian subcontinent. Indeed, although many workers had been recruited urgently from those regions while the war was raging, the government’s intention now was to return them to their home countries. As early as April 1945, a Colonial Office official, referring to around a thousand Caribbean workers in Merseyside and Lancashire, wrote that, because they were British, “we cannot force them to return”, but it would be “undesirable” to encourage them to stay.[2] But by the middle of 1947, the government had managed to deport most of them by administrative means and, when it came to discouraging new migrants, one highly questionable means used was the distribution in the Caribbean of an official film that showed

the very worst aspects of life in Britain in deep mid-winter. Immigrants were portrayed as likely to be without work and comfortable accommodation against a background of weather that must have been filmed during the appallingly cold winter of 1947-8.[3]

At the same time, however, the government was busy trying to recruit Poles in camps throughout the UK, displaced persons in Germany, Austria and Italy, people from the Baltic states and the unemployed of Europe. Anybody was more welcome than the Caribbean workers.

But there were pressures which made this position increasingly uncomfortable for the government: it became increasingly clear after the war that the British Empire was coming to an end and Britain began to seek good political and economic relations with the newly independent former colonies, most of which were becoming part of the new British Commonwealth. The government sought to reassure Commonwealth leaders of its goodwill by maintaining the status quo on immigration: the British Nationality Act 1948 confirmed the already-existing right of Commonwealth citizens to come to the “mother country” to live and work. Behind the scenes, however, the government was still determined to travel in the opposite direction.

Working parties

In 1947, the governors of Barbados, Jamaica, Trinidad and British Guiana, countries which had high unemployment rates, tried to persuade the British government that allowing some of their workers into Britain would be beneficial both to them and to Britain. In 1948, the Colonial Office responded by setting up an interdepartmental working party, the first of many set up during these years: the “Working Party on the Employment in the UK of Surplus Colonial Labour”. Its first task was to determine whether there was a prima facie case for using colonial workers to help in reconstructing the country. The working party seemed willing to take the broad hint being offered: it concluded that there was no overall shortage of labour in the UK after all and that the only sector of the economy that might benefit from colonial labour was the health sector.[4] The government, however, remained worried.

In 1953, a confidential meeting of ministers at the Colonial Office agreed that, before legislation to restrict immigration could be introduced, empirical evidence would be needed to justify it. Police surveillance of black communities was used for this purpose and surveys were undertaken by a wide range of government departments and voluntary organisations.[5] A working party on “The Employment of Coloured People in the United Kingdom” was set up. It studied the information provided to it by the government and produced a report in 1954. The cabinet was disappointed. After considering issues related to the number of immigrants in the country, employment and unemployment, housing and criminality, it failed to provide evidence to justify legislation. For some cabinet ministers, the working party had totally missed the point. Lord Salisbury declared that the working party did not seem to recognise “the dangers of the increasing immigration of coloured people into this country.”[6] He later spelt out his views even more clearly, declaring that “for me it is not merely a question of whether criminal negroes should be allowed in; it is a question of whether great quantities of negroes, criminal or not, should be allowed to come.”[7]

Many similar working parties and departmental and interdepartmental committees were set up in this post-war period, many of them overlapping in the tasks they were set. There was the “Interdepartmental Committee on colonial people in the United Kingdom”, based in the Home Office; the “Cabinet Committee on colonial immigrants”; and the one that seemed to express its discriminatory intentions most clearly in its title: the “Interdepartmental Working Party on the Social and Economic Problems Arising from the Growing Influx into the United Kingdom of Coloured Workers from Other Commonwealth Countries”. Nevertheless, none of these committees and working parties managed to produce convincing evidence to justify legislation. On the latter committee’s reports between 1959 and 1961, Spencer writes:

Viewed objectively, the reports of the Working Party consistently failed to fulfil the purpose defined in its title …. In the areas of public order, crime, employment and health there was little noteworthy to report to their political masters.[8]

Moreover, there was uncertainty within government circles about whether there was sufficient public support for immigration controls. In November 1954, Lord Swinton, the Colonial Secretary, wrote a memorandum expressing the hope that “responsible public opinion is moving in the direction of favouring immigration control”. There was, however, “a good deal to be done before it is more solidly in favour of it”.[9] In June 1955, Cabinet Secretary Sir Norman Brook wrote to Prime Minister Anthony Eden expressing the view that, while controls were obviously necessary, the government needed “to enlist a sufficient body of public support for the legislation that would be needed”.[10] So Caribbean workers continued to arrive. Indeed, since 1949, the new National Health Service (NHS) had begun recruiting nurses from the Caribbean. In 1956, London Transport began recruiting Caribbean staff. They came because they were needed. They came because they could. But trouble was brewing which might, in the end, give Eden and Brook what they wanted.

Smoke and mirrors – mission accomplished

The trouble had its roots in the new post-war world order and Britain’s position in it as a declining colonial power. As we have seen, the British were having to face the end of their Empire as one by one its old colonies achieved independence. For supporters of the British Empire, the saddest loss was India – over which Queen Victoria had proudly declared herself Empress – which became independent in 1947. Others were to follow. As Satnam Virdee notes of this period, “the limitations of Britain’s declining imperial reach were badly exposed by its seeming inability to repress movements for national independence in Kenya, Malaya and elsewhere.”[11] This process steadily changed Britain’s view of itself, and the consequences were given clear focus during the Suez crisis of 1956. Egypt, under President Nasser, had nationalised the Suez Canal. Britain had control over the canal at that time and regarded it as crucial to maintaining its pre-eminence in the Middle East. So Britain, together with France and Israel, invaded Egypt to take the canal back. The US refused to support the invasion, the UN intervened, and the invaders withdrew. “This episode”, writes Virdee, “had a devastating effect on British national confidence.”[12] As former US Secretary of State Dean Acheson would later express it poignantly: “Britain has lost an empire and not yet found a role.”[13] The consequences unfolded gradually. Two years after Suez, in the summer of 1958, there were riots in Nottingham (in the East Midlands) and in Notting Hill (in West London): “On successive nights, thousands of white people gathered in the streets of St Ann’s in Nottingham looking for black people to attack.”[14] In Notting Hill, “young white men attacked black residents and attempted to drive them off the streets …”[15] They were armed with “iron bars, butcher’s knives and weighted leather belts”[16] The black community armed themselves and responded.

The police downplayed any racist element in the attacks. DS Walters, in his official report, said the press was wrong to call the disturbances “racial riots”. He put most of the blame on “ruffians, with coloured and white” who engaged in “hooliganism”.[17] However, the reality was otherwise, as crowds of “300-400 white people in Bramley Road shouting, ‘We will kill all black bastards’ [told one police officer] ‘Mind your own business, copper. Keep out of it. We will settle these niggers our way. We’ll murder the bastards.’”[18] Likewise, the Foreign Office – in line with the government’s fears of offending Commonwealth governments – immediately played the riots down, telling its overseas diplomats to say that “by foreign standards” the disturbances would not even count as riots.[19] Nevertheless, “[i]n cases committed for trial, there were three white defendants for every black one.”[20] The racist attacks were encouraged and provoked by neofascist groups such as the Union Movement (led by Oswald Mosley, who had been leader of the British Union of Fascists in the 1930s), the White Defence League and the League of Empire Loyalists.[21] The problem for the government was that, however much it wanted to stop “coloured” immigration, if it was seen to do so in response to racist violence this would be equally offensive to Commonwealth governments and undermine Britain’s position as leader of the multicultural Commonwealth.

The government’s dilemma: how to conceal the racism behind its intended immigration controls? As we have seen, the working party with the clearest mandate to focus on “social and economic problems” consistently failed to construct an argument for controls which would do the job. So, in the end, working party officials concocted a solution: they compensated for their failure to find existing problems by predicting that they would arise in the future. They were, writes Spencer, “prepared to admit that the case for restriction could not ‘at present’ rest on health, crime, public order or employment grounds”,[22] but

[i]n the end, the official mind made recommendations based on predictions about … future difficulties which were founded on prejudice rather than on evidence derived from the history of the Asian and black presence in Britain.[23]

In 1961, Home Secretary R. A. Butler claimed, in a TV interview, that a decision on immigration controls would be made “on a basis absolutely regardless of colour and without prejudice.”[24] But he told the cabinet a very different story: when describing the work-voucher scheme at the heart of the government’s proposed Bill, he reassured them that “the great merit” of the scheme was

that it can be presented as making no distinction on grounds of race or colour … Although the scheme purports to relate solely to employment and to be non-discriminatory, the aim is primarily social and its restrictive effect is intended to, and would in fact, operate on coloured people almost exclusively.[25]

The Bill passed into law and became the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962, the first piece of legislation to control Commonwealth immigration after the war. The myth of a universal welcome should have died at that point.

[1] Hostile Environment: the Windrush Scandal: https://bobmouncer.blog/2025/03/22/hostile-environment-the-windrush-scandal-i/; https://bobmouncer.blog/2025/03/26/hostile-environment-the-windrush-scandal-ii/; https://bobmouncer.blog/2025/03/30/hostile-environment-the-windrush-scandal-iii/; https://bobmouncer.blog/2025/04/02/hostile-environment-the-mediterranean-scandal/;

[2] Spencer, I. (1997), British Immigration Policy since 1939: the Making of Multi-Racial Britain, Routledge, London, p. 39.

[3] Ibid., p. 32.

[4] Ibid., p. 40. Spencer cites National Archives, CO 1006/1, but this now seems to be unavailable.

[5] Carter, B., Harris, C. & Joshi, S. (1993), “The 1951-55 Conservative Government and the Racialization of Black Immigration”, in James, W. & Harris, C. (eds), Inside Babylon: The Caribbean Diaspora in Britain, Verso, London, pp. 58-59.

[6] National Archives, CAB 124/1191, Marquis of Salisbury, Minute, 8 August 1954.

[7] National Archives, CAB 124/1191, Marquis of Salisbury to Viscount Swinton, 19 November 1954.

[8] Spencer, I. (1997), British Immigration Policy since 1939: the Making of Multi-Racial Britain, Routledge, London, p. 119.

[9] Cited, ibid., p. 66.

[10] National Archives, PREM 11/824, briefing note, Norman Brook (Cabinet Secretary) to Prime Minister, 14 June 1955.]

[11] Virdee, S. (2014), Racism, Class and the Racialised Outsider, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, p. 107.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Cited, James Barber, “Britain’s place in the world”, British Journal of International Studies 6 (1980), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, p. 93: Britain’s Place in the World on JSTOR

[14] Virdee, S. (2014), Racism, Class and the Racialised Outsider, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, p. 108.

[15] Hilliard, C., “Mapping the Notting Hill riots”, History Workshop Journal, Vol. 93, \issue 1, Spring 2022, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 47-68.

[16] Travis, A. “After 44 years secret papers reveal truth about five nights of violence in Notting Hill”, The Guardian, 24 August 2002.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Virdee, S. (2014), Racism, Class and the Racialised Outsider, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, p. 108.

[19] Hilliard, C., “Mapping the Notting Hill riots”, History Workshop Journal, Vol. 93, \issue 1, Spring 2022, pp. 47-68: Mapping the Notting Hill Riots: Racism and the Streets of Post-war Britain | History Workshop Journal | Oxford Academic (oup.com)

[20] Ibid.

[21] Virdee, S. (2014), Racism, Class and the Racialised Outsider, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, p. 108.

[22] Spencer, op. cit., p. 120.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Playing the Race Card, BBC2 TV documentary, 24 October 1999.

[25] Hayter, T. (2000), Open Borders: The Case Against Immigration Controls, Pluto Press, London, p. 47.

The hostile environment: Labour’s response

In the first blog in this series (https://bobmouncer.blog/2025/03/22/hostile-environment-the-windrush-scandal-i/), I showed how the announcement of a “hostile environment” for migrants by UK Home Secretary Theresa May in 2012 led to suffering and trauma for thousands of people, the Windrush generation. In the second blog (https://bobmouncer.blog/2025/03/26/hostile-environment-the-windrush-scandal-ii/), I told the story of Hubert Howard, who was one of its victims. In the third blog (https://bobmouncer.blog/2025/03/30/hostile-environment-the-windrush-scandal-iii/), I showed how documents that could have prevented the disaster to Hubert and thousands of others were deliberately destroyed; I described how the scandal slowly emerged and the government’s obstinate refusal to roll back on the policy; and I showed how a compensation scheme was finally devised and how it failed so many Windrush victims. In the last blog (https://bobmouncer.blog/2025/04/02/hostile-environment-the-mediterranean-scandal/) I described the Mediterranean scandal, in which the EU, including the UK, stopped rescue operations in the Mediterranean and how a UK government tried to deny its responsibility for the ensuing tragedy.

In this blog, I examine Labour’s response to the hostile environment.

Labour’s response

The two major scandals examined in my previous blogs in this series unfolded, first, under a Tory/LibDem coalition government and then under the subsequent Tory government. But what was Labour’s response to May’s hostile environment? Maya Goodfellow describes it as “the most minimal resistance”.[1] Labour, the official opposition, abstained in the final Commons vote on the Immigration Bill. Sixteen MPs voted against it, but only six of them were Labour MPs: Diane Abbott, Kelvin Hopkins, John McDonnell, Fiona Mactaggart, Dennis Skinner and Jeremy Corbyn. Corbyn said the Bill was

dog-whistle politics, the mantras being that every immigrant is an illegal immigrant who must somehow be condemned, and that immigration is the cause of all the problems in our society … If we descend into a UKIP-generated xenophobic campaign, it weakens and demeans all of us and our society, and we are all the losers for that.[2]

One of the other MPs was Sarah Teather, a LibDem MP and former minister, who had told The Guardian in 2013 that the proposals in the Bill were “hewn from the same rock” as earlier welfare cuts, much of which were “about setting up political dividing lines, and trying to create and define an enemy”.[3] But apart from the six rebels, Labour MPs obeyed their leader, Ed Miliband, and the Labour whips, and abstained in the Commons vote.

By October, Miliband had moved further right. In a by-election campaign in the Rochester and Strood constituency, which UKIP was hoping to win, Miliband declared he would toughen immigration policy if Labour won the general election in May the following year.[4] Echoing Theresa May, he raised familiar spectres and fears about immigration, ignoring its advantages. The UK, he said, “needs stronger controls on people coming here” and promised a new immigration reform Act if he became Prime Minister. His message was:

- If your fear is uncontrolled numbers of illegal migrants entering the country, Labour will crack down on illegal immigration by electronically recording and checking every migrant arrive in or depart from Britain

- If your fear is of widespread migrant benefit fraud, Labour will make sure that benefits are linked more closely to workers’ contributions

- If the spectre that haunts you is, as Margaret Thatcher had put it, that immigrants were bringing an “alien culture” to Britain, Labour understands, and will ensure that migrants integrate “more fully” into society

- Miliband turned his attention to the EU. Arguments about Britain’s EU membership were coming to a head at this time, with both the Tory right and UKIP agitating for the UK to leave. In 2013, Prime Minister David Cameron had agreed to renegotiate Britain’s terms of membership. The renegotiation would be followed by an in/out referendum to take place after the 2015 general election. Miliband, in his by-election speech in 2014, included migration from the EU in his new immigration promises. He claimed that Labour under Tony Blair had wrongly opened the UK to Eastern Europeans when their countries had joined the EU in 2004. He would not let that happen again. If he won the 2015 election, there would be longer “transitional controls” for new EU members before they could move to Britain.

He even told the voters of Rochester and Strood that they didn’t need to vote for UKIP to get these policies: Labour would do the job.

One pledge seemed at first sight to be protective of migrants. Miliband said he wanted to ensure that migrants were not exploited by employers. However, this was, in fact, a reference to another fear – that migrant workers undercut native workers’ wages because bosses often pay lower wages to migrants (often below the minimum wage). However, where this problem exists, its solution lies not in immigration law but in employment law and its enforcement. It also lies in union recognition and legally binding agreements.

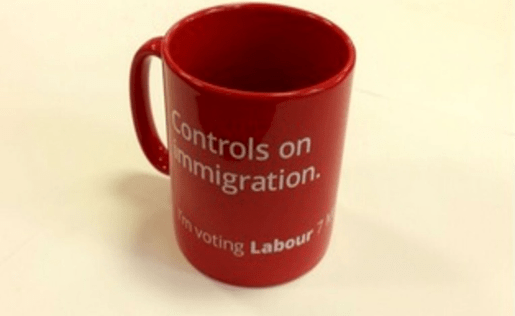

As promise followed promise and pledge followed pledge, Miliband began to sound like Theresa May. A few months later, as the 2015 election approached, Labour’s campaign included the issuing of mugs with “Controls on immigration” printed on them.

Labour’s immigration controls mug

None of this saved Miliband or his party, and the Tories won the 2015 election; the referendum vote in 2016 in favour of leaving the EU led to David Cameron’s resignation as Prime Minister; he was succeeded by Theresa May; Ed Miliband resigned as Labour leader; Jeremy Corbyn was elected in his place; the process of leaving the EU began. In 2017, Theresa May called another general election, hoping to increase her majority. In the event, the Tory party lost its small overall majority but won the election as the largest single party. But from then on it had to rely on Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) votes to get its business through the Commons.

These parliamentary changes meant nothing for the Windrush generation. The scandal began to come to light in 2017 but their suffering continued beyond the end of the decade, one of the main reasons being that the compensation scheme was seriously flawed. This remained a problem in April 2025, almost a year after the election of a Labour government. The Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman (PHSO), Rebecca Hilsenrath, had found that

further harm and injustice are still being caused by failings in the way the scheme is working. We found recurrent reasons for this, suggesting these were not one-off issues but systemic problems.[5]

In response, the Home Office sought to give some reassurance:

This government is committed to putting right the appalling injustices caused by the Windrush scandal and making sure those affected receive the compensation they rightly deserve.[6]

Nevertheless, given the Home Office’s record, we should hesitate before we are reassured. In 2020, the Williams review of the Windrush scandal had made 30 recommendations to the government, all of which were accepted by Priti Patel, Tory Home Secretary at the time. In January 2023, the Home Office unlawfully dropped three of them.[7] Moreover, the department prevented the publication of a report prepared in response to the Williams Review. Williams had said that Home Office staff needed to “learn about the history of the UK and its relationship with the rest of the world, including Britain’s colonial history, the history of inward and outward migration and the history of black Britons.” As a result, the Home Office commissioned an independent report: The Historical Roots of the Windrush Scandal. In the words of Jim Dunton, the report

lays much of the blame for the Windrush scandal on essentially racist measures introduced to restrict the ability of Commonwealth citizens to move to the UK in the years since the second world war.[8]

The report has been available internally since 2022 but, writes Dunton, “the department resisted attempts for it to be made publicly available, including rejecting repeated Freedom of Information Act requests and pressure from Labour MP Diane Abbott.” Then, in early September 2024, after a legal challenge was launched,

a First Tier Tribunal judge ordered the document’s publication, quoting George Orwell’s memorable lines from 1984: “Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past.”[9]

So the Home Office, reluctantly, made the report publicly available, and I will refer to its findings in future blogs. But it is not yet time to take Home Office reassurances at face value. Or Labour’s reassurances, come to that.

In future blogs: more on Labour’s record on immigration and race; and the necessary exposure of a long-standing myth.

[1] Goodfellow, M. (2019), Hostile Environment: How immigrants became Scapegoats, Verso Books, London, loc. 167.

[2] Jack Peat, “Just 6 Labour MPs voted against the 2014 Immigration Act”, The London Economic, 19/04/2018:

[3] Decca Aitkenhead, “Sarah Teather: ‘I’m angry there are no alternative voices on immigration’.”, The Guardian, 12 July 2013.

[4] Andrew Grice, “Ed Miliband attempts to take on Ukip – with toughened immigration policies”, The Guardian, 24 October 2014: Ed Miliband attempts to take on Ukip – with toughened immigration policies | The Independent | The Independent

[5] Adina Campbell, “Payments for Windrush victims denied compensation”, BBC News, 5 September 2024: Payments for Windrush victims denied Home Office compensation – BBC News

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ashith Nagesh & André Rhoden-Paul, “Home Office unlawfully axed Windrush measures”, BBC News, 19 June 2024: Windrush Scandal: Home office unlawfully axed recommendations, court rules – BBC News

[8] Jim Dunton, “Home Office publishes internal ‘roots of Windrush’ report after FoI battle”, Civil Service World, 27 September 2024: Home Office publishes internal ‘roots of Windrush’ report after FoI battle

[9] Ibid.

Hostile environment: the Mediterranean scandal

In the first blog in this series (https://bobmouncer.blog/2025/03/22/hostile-environment-the-windrush-scandal-i/), I showed how the announcement of a “hostile environment” for migrants by UK Home Secretary Theresa May in 2012 led to suffering and trauma for thousands of people, the Windrush generation. In the second blog (https://bobmouncer.blog/2025/03/26/hostile-environment-the-windrush-scandal-ii/), I told the story of Hubert Howard, who was one of its victims. In the third blog, I showed how documents that could have prevented the disaster to Hubert and thousands of others were deliberately destroyed; I described how the scandal slowly emerged and the government’s obstinate refusal to roll back on the policy; and I show how a compensation scheme was finally devised and how it failed so many Windrush victims. In this blog, I tell how another scandal erupted involving the UK government, though this time it was an EU-wide scandal. It was, however, perfectly in line with the UK’s hostile environment policy toward migrants. It should be counted as part of it.

The Mediterranean scandal

David Cameron and Theresa May were part of another immigration scandal, though they were not the only ones involved. In October 2014, Italy brought its routine search-and-rescue operations (called Mare Nostrum) to an end. The scheme rescued migrants crossing the Mediterranean Sea from Libya, most of them in unseaworthy boats. In the 12 months between October 2013 and October 2014, according to the Commons Home Affairs Select Committee, “Mare Nostrum saved 100,000 lives, but the Italian Government could not afford to maintain the operation at the cost of €9 million a month”[1] and had, for some time, been pressing the EU (which still included the UK as a member-state) to play a larger role in the operation. When Mare Nostrum came to an end, the EU’s response was to replace the Italian scheme with its own much more limited scheme, Triton. The difference between the two schemes was that Mare Nostrum undertook “a proactive search and rescue operation across 27,000 square miles of sea”[2] whereas, under Triton, the EU simply operated a coastguard patrol that reached out no further than 12 miles from the coast. Routine search-and-rescue operations were over. The EU argued that the search-and-rescue operations represented a “pull factor” for migrants: they attempted the dangerous crossing because they thought they would be rescued if they got into difficulties.

The Home Office carefully sheltered under the EU roof as officials sought to justify the removal of search and rescue: “Ministers across the EU”, the Home Office said,

have expressed concerns that search-and-rescue operations in the Mediterranean … [are] encouraging people to make dangerous crossings in the expectation of rescue. This has led to more deaths as traffickers have exploited the situation using boats that are unfit to make the crossing.[3]

One year later, Cameron and his Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg (leader of the Liberal Democrats), admitted that Triton was flawed. As the EU had scaled back the search-and-rescue operations to no more than coastguard patrols, hundreds more people had died. Then, after two disasters in quick succession in which a total of 1,200 people had died, Cameron declared that the plan to reduce crossings and deaths was “not successful”. He then sought to distance himself from it as much as possible by stressing the EU’s role as if it had nothing to do with him: the decision to stop search and rescue, he said,

was made by the EU and Italy as well. They found at some stage it did look like more people were taking to boats. So they, the EU, decided to end that policy and have a coastguard policy. That hasn’t worked either.[4]

It is worth noting that the decision to stop search and rescue was not a joint decision between Italy and the EU: the decision was at first made, as we have seen, by Italy alone on grounds of cost.[5] Nevertheless, the EU’s earlier unwillingness to play a larger role contributed to Italy’s decision.

Like Cameron, Nick Clegg also managed to distance himself from the policy in an attempt to avoid blame being attached to him or his party: he too claimed the decision to stop search and rescue was taken by “the EU”. He also claimed credit for the Liberal Democrats, who had, he said, called for an urgent review of “the EU’s policy”:

The EU’s decision to end routine search-and-rescue operations in the Mediterranean last year was taken with good intentions. No one expected the number of deaths to fall to zero, but there was a view that the presence of rescue ships encouraged people to risk the crossing. That judgment now looks to have been wrong. That’s why the Liberal Democrats have called for an urgent review of the EU’s policy …[6]

Once the consequences of the removal of search and rescue had become clear and public, the EU rolled back on the disastrous “coastguard patrols only” policy: it introduced a new search-and-rescue policy and Cameron pledged ships and helicopters and ordered the Royal Navy flagship HMS Bulwark to Malta to join the operations. This was a U-turn and it involved a significant change in the government’s language: its policy in the Mediterranean was now about “rescuing these poor people” rather than depicting them as reckless and foolish migrants.[7] But by June that year it was announced that the deployment of HMS Bulwark was being reviewed, which raised the question that, if it was to be withdrawn, would it be replaced? On 17 June, Labour MP Hilary Benn asked Chancellor George Osborne, who was standing in for Cameron at Prime Minister’s Questions in the Commons:

… we learned yesterday that [HMS Bulwark’s] deployment is under active review. Having made a grave error last October in withdrawing support from the Mare Nostrum search and rescue operations, will the right hon. Gentleman assure the House that the Government will continue to save the lives of those in peril on that sea?[8]

Osborne replied that “no one should in any way doubt Britain’s determination to play its role in helping with this situation”:

Taking people out of the water and rescuing them is essential – we are a humanitarian nation and we need to deal with those issues – but, in the end, we must break the link that enables someone to get on a boat and then claim asylum in Europe and spend the rest of their lives on the European continent.[9]

The government’s priorities became clearer on 22 June when Defence Secretary Michael Fallon announced that HMS Bulwark (19,000 tonnes, 176 metres long; 3,000 lives saved, according to government figures[10]) was to be replaced by HMS Enterprise (3,700 tonnes, 90.6 metres long, able to hold up to 120 people; part of the government’s “intelligence-led effort” to solve the crisis).[11] Despite this obvious reduction in search-and-rescue capacity and the priority it was given, Downing Street said that HMS Enterprise would be gathering intelligence “while continuing to rescue people as necessary”. However, one month later Enterprise had “not rescued any migrants since deploying to the Mediterranean to support the common security defence policy operation”.[12] So “rescuing these poor people” had apparently ceased to be “absolutely essential” and had given way to intelligence gathering. From now on, intelligence would be gathered while search-and-rescue operations vanished entirely.

[1] Migration Crisis (2015), Report by the Commons Home Affairs Select Committee, paras. 79-81: House of Commons – Migration Crisis – Home Affairs Committee (parliament.uk)

[2] Home Affairs Committee, House of Commons, Migration Crisis:

[3] Alan Travis, “Home Office defends decision for UK to halt migrant rescues”, The Guardian, 28 October 2014.

[4] Rowena Mason, “Cameron and Clegg admit axing search and rescue in Mediterranean has failed”, The Guardian, 22 April 2015: Cameron and Clegg admit axing search and rescue in Mediterranean has failed | Immigration and asylum | The Guardian

[5] Home Office minister James Brokenshire confirmed this in an answer during an urgent question in the House of Commons, when a Tory MP had suggested that the EU had withdrawn support from Mare Nostrum: ”To be clear, the EU is not withdrawing anything. Mare Nostrum is an Italian initiative. It is supported by the Italian navy, and ultimately decisions will be taken by the Italian Government.” (Refugees and Migrants (Search and Rescue Operation) (Urgent Question), col. 404, 30 October 2014: Refugees and Migrants (Search and Rescue Operation) – Hansard – UK Parliament

[6] Nick Clegg, “The solution to the deaths in the Mediterranean lies on land, not at sea”, The Guardian, 22 April 2015: The solution to the deaths in the Mediterranean lies on land, not at sea | Nick Clegg | The Guardian

[7] Ian Traynor, “European leaders pledge to send ships to Mediterranean to pick up migrants”, The Guardian, 23 April 2015: European leaders pledge to send ships to Mediterranean to pick up migrants | European Union | The Guardian

[8] Commons Hansard, “Prime Minister’s Questions”, 17 June 2015, col. 312: House of Commons Hansard Debates for 17 Jun 2015 (pt 0001) (parliament.uk)

[9] Ibid.

[10] HMS Enterprise to replace HMS Bulwark in the Mediterranean, Ministry of Defence: HMS Enterprise to replace HMS Bulwark in the Mediterranean – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

[11] Ibid.

[12] Alan Travis, “HMS Bulwark’s replacement yet to rescue any migrants in Mediterranean”, The Guardian, 27 July 2015HMS Bulwark’s replacement yet to rescue any migrants in Mediterranean | Migration | The Guardian:

Hostile environment: the Windrush scandal III

The first blog in this series (https://bobmouncer.blog/2025/03/22/hostile-environment-the-windrush-scandal-i/), I showed how the announcement of a “hostile environment” for migrants by UK Home Secretary Theresa May in 2012 led to suffering and trauma for thousands of people, the Windrush generation. In the second blog (https://bobmouncer.blog/2025/03/26/hostile-environment-the-windrush-scandal-ii/), I told the story of Hubert Howard, who was one of its victims. In this third blog, I show how documents that could have prevented the disaster to Hubert and thousands of others were deliberately destroyed. I describe how the scandal slowly emerged and the government’s obstinate refusal to roll back on the policy; and I show how a compensation scheme was finally devised and how it failed so many Windrush victims.

Sabotage?

The passports held by the Windrush arrivals in 1948, and by those who arrived in subsequent years, eventually expired, and many were never renewed and were later lost. Moreover, many of the children who travelled with their parents did so on their parents’ passports and subsequently had none of their own. This did not pose any problems – until they were asked to provide documentation to prove their status. The government refused to accept work records, tax and National Insurance or NHS records as evidence of citizenship. Yet if a lack of passports was the problem, there were other documents that could have been used to solve it: the landing cards completed by the Windrush passengers during their voyage, which they presented to immigration staff on arrival, The cards had been carefully collected and eventually stored in a basement room at the Home Office. According to BBC News, they were later “used by officials to help subsequent generations to prove they had a right to remain in the UK.”[1] But, in 2010, the Home Office destroyed them.[2] Once they were destroyed, members of the Windrush generation and their descendants discovered they had no way of proving their legal status.

Passing the buck

The decision to physically destroy the landing cards was taken in October 2010, under the Tory/LibDem coalition government when Theresa May was Home Secretary. In April 2018, however, when she was Prime Minister, she was questioned about the decision by Jeremy Corbyn in the House of Commons:

Corbyn: “Did the Prime Minister – the then Home Secretary – sign off that decision?”

May: “No. The decision to destroy the landing cards was taken in 2009 under a Labour government.”[3]

May had avoided the question, which was about her responsibility for the 2010 decision to physically destroy the landing cards. Instead, attempting to put the blame on Labour, she diverted attention to what seems to have been the original decision-in-principle, taken in 2009.[4] According to the Home Office, that decision was an administrative decision taken in the context of the digitalisation of Home Office files. The UK Border Agency had approved a business case to get rid of paper records, including the cards.[5] Under the Data Protection Act 1998, personal information should only be kept for long periods if it is strictly necessary to do so. According to the UK Border Agency in 2018, its judgement in 2009 had been that “the information on the [boarding cards] was of limited value and not sufficient to justify continued retention.”[6] This judgement seems to have been made despite their proved usefulness in determining status.

So far, it looks as if these decisions were made by officials, behind closed doors, without the direct involvement of politicians. Indeed, while May was avoiding Corbyn’s question, her spokesperson in Downing Street helpfully claimed that the decision to actually do a destruction job on the landing cards in 2010 was also an “operational decision”, implying that Theresa May was not involved.[7] Not surprisingly, Labour politicians also hastened to deny any past involvement: Alan Johnson, Labour Home Secretary in 2009, said it was “an administrative decision”.[8] Johnson said he “had absolutely no recollection at all of being involved” in the landing cards decision.[9] Jacqui Smith, his predecessor at the Home Office until June of that year, said it was “not a policy decision she had made”.[10]

Doubts about politicians’ claims of innocence, however, were raised by Lord Kerslake, a former head of the civil service. He told BBC Newsnight that “the Borders Agency was effectively part of the civil service and it took its advice and direction from ministers.”[11] It was, he said, “pretty unlikely” that the Home Office would destroy records. “But the truth is we don’t know,” he said. “We need to investigate this in more detail to understand what happened.” Nevertheless, whoever was ultimately responsible, irreversible decisions had been made, with dire consequences for the Windrush generation.

The gathering storm

The plight of the Windrush victims was slow to emerge. But public awareness grew, largely due to press reports about individuals. The Guardian began to publish the results of its major investigation in late 2017. In February 2018, the Jamaican High Commissioner in London, Seth George Ramocan, said, “In this system one is guilty before proven innocent rather than the other way around,” and joined with other Caribbean diplomats in calling on the government to be “more compassionate”.[12] There was widespread anger at the plight of Albert Thompson when he was denied cancer treatment. On 21 March, at Prime Minister’s questions in the House of Commons, Theresa May refused to intervene in his case, saying it was the responsibility of the hospital to make the decision. About Albert himself she said he needed to “evidence his settled status in the UK.”[13] May insisted on this despite mounting evidence that none of these people had ever been “illegal migrants” and despite the disastrous consequences of the hostile environment policy on all its Windrush generation victims.

On 15 April 2018, during the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) in London, Downing Street refused a formal request by the High Commissioners of 12 Caribbean Commonwealth countries for a meeting between their heads of government and Theresa May to discuss the Windrush scandal.[14] Pressure on the government increased and Home Secretary Amber Rudd apologised in the House of Commons for the way people had been treated. Bizarrely, she blamed Home Office officials for being too focused on policy. They had, she said, forgotten the importance of the individual.[15] The next day, May made an unconvincing – indeed, confusing – apology to the Caribbean leaders gathered at the summit. She told them her government was not “clamping down on Commonwealth citizens”. It was all the fault of the new rules (which she herself had introduced) which had “resulted in some people, through no fault of their own, now needing to be able to evidence their immigration status.” She did not, however, offer to abolish those rules or to roll back on her demand that Albert Thompson should “evidence his settled status in the UK”. Instead, she declared that “the overwhelming majority of the Windrush generation do have the documents that they need, but we are working hard to help those who do not.”[16] None of these apologies and promises would make any difference to the Windrush victims.

Smoke and mirrors

Amber Rudd resigned as Home Secretary two weeks later, after denying knowledge of Home Office deportation targets, some of which she had herself proposed to Theresa May. On 30 April, Sajid Javid, her replacement as Home Secretary, gave the hostile environment a new name. He explained:

I don’t like the phrase hostile. So the terminology is incorrect and I think it is a phrase that is unhelpful … [The policy] is about a compliant environment and it is right that we have a compliant environment.[17]

This word game was meaningless. It was an exercise in smoke and mirrors in which nothing changed: the Windrush victims were still “illegal”, with “no right to be here”. Like Theresa May and Amber Rudd before him, Javid wanted to maintain a hostile environment. Giving it a new name did nothing for its victims, who had been legal and “compliant” since the day they arrived in the country – or, in the case of their descendants, since the day they were born. Javid pledged to “do whatever it takes to put [the situation] right”; he even claimed that because of his own Asian background[18] he was “personally committed to and invested in resolving the difficulties faced by the … Windrush generation.”[19] But he gave no sign the policy would change in anything other than its meaningless new name. As Labour MP Stella Creasy tweeted while he was still answering questions in the House of Commons:

Just told the new Home Secretary whether he calls it compliant or hostile, it’s deeds not words that matter in how he treats Windrush generation.[20]

Compensation

The details of the Windrush scandal began to emerge in 2017. The Windrush Scheme, established in 2018. enabled more than 13,800 victims of the scandal to receive documentation confirming their legal status as citizens. But they had received no compensation for their unjust treatment, and the ruin it had brought to their lives. But in 2019 the Windrush Compensation Scheme seemed to promise some redress to the Windrush generation. Unfortunately, as the Commons Home Affairs Select Committee reported in December 2021, “instead of providing a remedy, for many people the Windrush Compensation Scheme has actually worsened the injustices faced as a result of the Windrush scandal.”[21] For one thing, the Home Office seemed unable to decide how many victims there were. The Committee reported that “four years after the Windrush scandal broke, the Government does not have a confirmed figure for the total number of people affected.”[22] The Home Office’s original assessment was that there would be 15,000 eligible claims. But in February 2020 a “revised impact assessment” was given which reduced the number to 11,500. In July 2021, the Home Secretary announced another reduction: now the numbers were somehow between 4,000 and 6,000. The reasons for this reduction were unclear, based as it was on “information from the Windrush Scheme and the Windrush Compensation Scheme, but also using some judgement where information is limited.”[23] The meaning of “using some judgement” is not clear. The Committee identified “a litany of flaws in the design and operation of the Windrush Compensation Scheme.”[24] The scheme placed “an excessive burden on claimants to produce documentary evidence of the losses they suffered.”[25] This obsession with documentation, or the lack of it, was the same obsession that denied its victims citizenship status in the first place. Clearly no lessons had been learned in the intervening period. There were also “long delays in processing applications and making payments, and inadequate staffing of the scheme; a failure to provide urgent and exceptional payments to individuals in desperate need.”[26] There were delays in supporting grassroots campaigns designed to reach eligible claimants. Given the nature of the Windrush scandal as a consequence of the hostile environment policy, we should not assume the Home Office’s goodwill or trust its changing numbers. Moreover, on the question of numbers, many thousands suffered from the effects of having their citizenship status wrongly denied and, not surprisingly, attention has tended to focus on the Caribbean Windrush generation. But, the Committee noted,

people from other Commonwealth and non-Commonwealth countries have also been affected. The children and grandchildren of people who could not evidence their lawful status have also faced difficulties.[27]

The Committee summarised the failure of the Windrush Compensation Scheme as of November 2021:

Our inquiry found that the vast majority of people who have applied for compensation have yet to receive a penny: for some, the experience of applying for compensation has become a source of further trauma rather than redress, and others have been put off from applying for the scheme altogether. We are deeply concerned that as of the end of September, only 20.1% of the initially estimated 15,000 eligible claimants have applied to the scheme and only 5.8% have received any compensation. It further compounds the Windrush scandal that twenty-three individuals have died without receiving compensation for the hardship they endured.[28]

By June 2023, 34 had died. The Committee also noted that “the design and operation of this scheme contained the same bureaucratic insensitivities that led to the Windrush scandal in the first place.” This was, it said, “a damning indictment of the Home Office, and suggests that the culture change it promised in the wake of the scandal has not yet occurred.”[29]

But the Windrush scandal was not the only scandal of the hostile environment. David Cameron and Theresa May were part of another scandal that emerged from the policy, one which also caused immense suffering and was responsible for many deaths. More of that in the next blog.

[1] “Windrush Investigation urged over landing cards”, BBC News, 19 April 2018: Windrush: Investigation urged over landing cards – BBC News

[2] Windrush: Theresa May hits back at Labour over landing cards”, BBC News, 28 April 2018 Windrush: Theresa May hits back at Labour over landing cards – BBC News

[3] Cited, Liz Bates, “Decision to destroy Windrush landing documents taken under Labour, insists Theresa May” PoliticsHome, 18 April 2018: Decision to destroy Windrush landing documents taken under Labour, insists Theresa May

[4] Windrush: Theresa May hits back at Labour over landing cards”, BBC News, 28 April 2018 Windrush: Theresa May hits back at Labour over landing cards – BBC News

[5] “Who destroyed the Windrush landing cards?”, Channel 4 News FactCheck: FactCheck: who destroyed the Windrush landing cards? – Channel 4 News

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] “Windrush: Alan Johnson says landing cards decision was made in 2009”, BBC News, 20 April 2018: Windrush: Alan Johnson says landing cards decision was made in 2009 – BBC News

[9] Windrush: Theresa May hits back at Labour over landing cards”, BBC News, 28 April 2018 Windrush: Theresa May hits back at Labour over landing cards – BBC News

[10] Ibid.

[11] “Windrush Investigation urged over landing cards”, BBC News, 19 April 2018: Windrush: Investigation urged over landing cards – BBC News

[12] Gentleman, A., “Caribbean diplomats ask UK for more compassion for citizens”, The Guardian, 22 February 2018: Caribbean diplomats ask UK for more compassion for citizens | Immigration and asylum | The Guardian

[13] Gentleman, A., “Windrush U-turn is welcome, but May’s policy was just cruel”, 16 April 2018: Windrush U-turn is welcome, but May’s policy was just cruel | Immigration and asylum | The Guardian

[14] Gentleman, A. “No 10 refuses Caribbean request to discuss children of Windrush”, The Guardian, 15 April 2018: No 10 refuses Caribbean request to discuss children of Windrush | Commonwealth immigration | The Guardian

[15] Gentleman, A., “The week that took Windrush from low-profile investigation to national scandal”, The Guardian, 20 April 2018. The week that took Windrush from low-profile investigation to national scandal | Commonwealth immigration | The Guardian

[16] “Windrush generation: Theresa May apologises to Caribbean leaders”, BBC News, 17 April 2018: Windrush generation: Theresa May apologises to Caribbean leaders – BBC News

[17] Steven Poole, “Compliant environment’: is this really what the Windrush generation needs?”, The Guardian, 3 May 2018: ‘Compliant environment’: is this really what the Windrush generation needs? | Reference and languages books | The Guardian

[18] Javid was born in Rochdale, Lancashire, to a British Pakistani family

[19] Andrew Sparrow, “Sajid Javid disowns ‘hostile environment’ phrase in first outing as home secretary”, The Guardian, 30 April 2018: Sajid Javid disowns ‘hostile environment’ phrase in first outing as home secretary – as it happened | Amber Rudd | The Guardian

[20] Twitter post, @stellacreasy, 30 April 2018.

[21] House of Commons Home Affairs Select Committee Report, 7 December 2021: The Windrush generation has been failed by the Compensation Scheme (shorthandstories.com)

[22] The Windrush Compensation Scheme, House of Commons Home Affairs Committee Report (24 November 2021), para 9: The Windrush Compensation Scheme – Home Affairs Committee (parliament.uk)

[23] Letter to Yvette Cooper MP, Chair of the Home Affairs Select Committee, from Home Secretary Priti Patel MP (20 July 2021).

[24] The Windrush Compensation Scheme, House of Commons Home Affairs Committee Report (24 November 2021), Summary: The Windrush Compensation Scheme – Home Affairs Committee (parliament.uk)

[25] Ibid., para. 9.

[26] Ibid.

[27]Ibid., para 2.

[28] Ibid., Summary.

[28]Ibid., para 2.

[28] Ibid., Summary.

[29] Ibid.

Hostile environment: the Windrush scandal II

The first blog in this series[1] showed how the announcement of a “hostile environment” for migrants by UK Home Secretary Theresa May in 2012 led to suffering and trauma for thousands of people, the Windrush generation. In this second blog, I tell the story of Hubert Howard, who was one of its victims.

Hubert Howard

We begin Hubert’s story in 1960, when his mother brought him to the UK from Jamaica when he was three years old. They were Citizens of the United Kingdom and Colonies (CUKCs), and Commonwealth citizens, and thus had the right to enter and reside in the UK. In his Court of Appeal hearing in 2019, Lord Justice Underhill made clear that Hubert’s residence, “was lawful from his first arrival in 1960.”[2] When Jamaica gained independence in 1962, Hubert automatically acquired Jamaican nationality (and thus ceased to be a CUKC). But he remained a Commonwealth citizen. This meant, Underhill explained, that “his right to reside in the United Kingdom was unaffected.”[3] Nevertheless, as we have seen,[4] the Acts of 1981 and 1988 did undermine that right. In particular, the British Nationality Act 1981 removed Hubert’s status as citizen and turned him into a foreigner. It imposed a limited transition period of five years during which individuals like Hubert would have to register themselves as British if they wanted to stay British. In her Windrush Lessons Learned Review, Wendy Williams noted that the transition period ended on 31 December 1987.[5] Once that period had expired the only way for Hubert to regain his legality and British status was through naturalisation.

Many of the Windrush generation, however, neither registered nor applied for naturalisation.[6] There were several reasons for this: the Home Office was afraid it would not be able to cope with the numbers that would apply and, the Williams Review found, it “wanted to develop advertising that was informative but didn’t ‘stimulate a flood of enquiries’.”[7] Moreover, officials managed the numbers by telling some applicants that “they didn’t have to register and wouldn’t face removal if they withdrew their applications.”[8] A leaflet issued in 1987 advised:

If you have the right to register but you don’t want to, you do not have to. Your other rights in the United Kingdom will not change in any way. You will not lose your entitlement to social benefits, such as health services, housing, welfare and pension rights, by not registering. Your position under immigration law is not changed.[9]

In the light of what happened later, when the Windrush victims lost all those entitlements, this piece of disinformation is startling. Regrettably, but not surprisingly, some people accepted the advice and did not register. Williams also highlighted another disincentive: applications “cost £60 (approximately £180 in today’s prices), with no dispensation for people on benefits.”[10] But not least among the reasons for not registering themselves as British or applying for naturalisation was that the Windrush generation took it for granted that they didn’t need to: they had come to the “mother country”, they were already British.[11] So, although around 130,000 people did apply for citizenship, many let the deadline pass.[12] One of them was Hubert Howard.

When Hubert’s mother retired, she decided to return to Jamaica. In 2005 she became ill with cancer and Hubert applied for a passport so he could visit her. His application was refused because, in the view of the Home Office, he had no documentary proof of his British citizenship. In 2006, his mother died, and he applied again so that he could go to her funeral. His application was again refused. In the end, he was never able to visit her grave. (This means, of course, that his legal rights as a member of the Windrush generation were being denied long before the hostile environment was announced in 2012, and we will return to this point in a later blog.) Hubert made several subsequent attempts to obtain confirmation of his status. After one of them, in 2011 (by which time Hubert had had 51 years of residence and a long work record), the Home Office wrote to him:

You confirmed that you entered the UK in the 1960s as a child and have lived in the UK since that time, but you are uncertain of your immigration status. In order to apply for British citizenship, you will first need to obtain confirmation of your immigration status in the UK based on your residence here.[13]