Home » Posts tagged 'immigration controls'

Tag Archives: immigration controls

Labour, immigration and Enoch Powell

Introduction

In an earlier blog, we saw how working parties were set up after the Second World War whose task was to justify racist immigration controls.[1] They repeatedly failed to do so, but they continued their efforts for 17 years. Finally, employing a series of manifestly false arguments, the Tories passed the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962, complete with racist controls.

Hostility to black Commonwealth immigrants, however, was not confined to the Tories. It was, after all, the Labour government elected in 1945 that set up the working parties in the first place. Kieran Connell writes of “the relentless presence of racism in 1940s Britain, and the related influence of ideas about race.”[2] Labour was part of that pressure and influence. In 1946, Labour Home Secretary Chuter Ede told a cabinet committee that when it came to immigration he would be much happier if it “could be limited to entrants from the Western countries, whose traditions and social backgrounds were more nearly equal to our own.”[3] When the Empire Windrush arrived in 1948 with 492 Jamaicans ready to work to rebuild post-war Britain, 11 Labour MPs wrote to Prime Minister Clement Attlee, notifying him of “the fact that several hundred West Indians have arrived in this country trusting that our government will provide them with food, shelter and employment.” They feared that “their success might encourage other British subjects to follow their example.” This would turn Britain into

an open reception centre for immigration not selected in relation to health, education and training and above all regardless of whether assimilation was possible or not … An influx of coloured people domiciled here is likely to impair the harmony, strength and cohesion of our public and social life and cause discord and unhappiness among all concerned.[4]

Attlee replied to the letter, reassuring them that “if our policy [of unrestricted immigration] were to result in a great influx of undesirables we might, however unwillingly, have to consider modifying it.”[5] Kenan Malik notes that this exchange of letters contains many assumptions that shaped official and popular attitudes to post-war black immigration:

There are two kinds of British citizens: white people and “undesirables”. Britain is in danger of being swamped by immigrants taking advantage of the nation’s generosity. Immigrants’ standards of “health, education and training” are lower than those of British people. Black people are incapable of assimilating British culture. A large black presence in Britain would create social tensions.[6]

Such attitudes didn’t end with that decade but continued through the 17 years to 1962. At first, therefore, it seems puzzling that Labour opposed the 1962 Act throughout its passage through parliament. It did so, however, in the context of the ending of British rule in countries that were previously part of the British Empire and were now becoming independent nations. Britain’s post-war determination to justify immigration controls against black immigrants now came up against its need to build Commonwealth institutions and keep a political and economic foothold in the countries it once ruled. To that end, the Commonwealth was increasingly promoted as a “family of nations”. Any suggestion that the racism that had served British interests “out there” in the old Empire might now be applied to citizens of the new Commonwealth when they came here could threaten the whole project. This was a dilemma for both the main political parties. Lord Salisbury (Lord President of the Council and Tory Leader of the House of Lords) was a strong advocate of immigration controls. When a working party reported that there was no evidence that black immigrants were more inclined to criminality than white natives, he roundly declared in 1954: “It is not for me merely a question of whether criminal negroes should be allowed in … it is a question of whether great quantities of negroes, criminal or not, should be allowed to come.”[7] Lord Swinton (Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations) agreed but warned Salisbury of the dangers ahead: “If we legislate on immigration, though we can draft it in non-discriminatory terms, we cannot conceal the obvious fact that the object is to keep out coloured people.”[8] Other Tories were more cautious. Henry Hopkinson, Minister of State at the Colonial Office, declared: “We still take pride in the fact that a man can say civis Britannicus sum [I am a British citizen] whatever his colour may be and we take pride in the fact that he wants to and can come to the mother country.”[9] In 1958, Arthur Bottomley, on Labour’s front bench, had also spoken up for the new Commonwealth and against immigration controls:

The central principle on which our status in the Commonwealth is largely dependent is the “open door” to all Commonwealth citizens. If we believe in the importance of our great Commonwealth, we should do nothing in the slightest degree to undermine that principle.[10]

It seemed for a while as if the battle between racist immigration controls, espoused by both parties, and the Commonwealth ideal of a “family of nations”, also espoused by both parties, might be won by the Commonwealth. But when Labour won the 1964 general election, the new government immediately refocused on immigration controls and increased the restrictions in the 1962 Act. In the years to come, Labour would introduce legislation and rules to reduce black immigration whenever it got the chance.

Facing both ways

Labour in government dealt with the embarrassing contradiction between racism and the “Commonwealth ideal” by facing both ways and hoping nobody would notice. It constantly sought to reassure voters that it “understood” their “genuine concerns” about immigration and enacted increasingly restrictive immigration laws. At the same time, it denied being racist and passed legislation aimed at creating “good race relations”. What often emerged from this process, however, were weak race-relations laws, suggesting that the government’s priority was to curb immigration. Thus, the Race Relations Acts of 1965 and 1968 were half-hearted affairs. While the 1965 Act did prohibit “incitement to racial hatred”, when it came to discrimination it didn’t include discrimination in housing and employment, and it didn’t apply to the police; and while the 1968 Act went further and included discrimination in housing and employment, the government decided that this would not apply to the police, who had exerted strong pressure on the cabinet not to include them. Home Secretary James Callaghan told the cabinet at the time:

The opposition of the Police Federation to amending the [police disciplinary] code has been intense and deep-seated. And the Police Advisory Board has been unanimous in advising me not to proceed.[11]

In 1968, the government introduced a new Commonwealth Immigrants Act which seemed set to undo the limited good the two Race Relations Acts had done. The Act refused all Commonwealth immigrants entry into the UK unless they could prove they were – or one of their parents or grandparents was – born, naturalised or adopted in the UK, or unless they were otherwise registered in specified circumstances as UK citizens.[12] This meant that citizens in the “white” Commonwealth (Canada, Australia, New Zealand) were not refused entry. The Act was Labour’s response to the Kenyan Asians crisis, when racism on the far right of the Tory Party was at its most virulent and dangerous. It was a decision to follow the Tory racists.

The Kenyan Asians: race, nation and the end of Empire

The Kenyan Asians were being forced out of Kenya by its government’s Africanisation policy, which excluded Kenya’s Asian population from employment and other rights. Many of them had British passports, which a British Conservative government had allowed them to retain following Kenya’s independence in 1963. Now, not surprisingly, they expected to be able to use them. The Labour government, however, decided otherwise. 80,000 of them, out of a total of about 200,000, had arrived in Britain by early 1968 and the government had been under pressure from several directions to keep them out. A campaign against allowing them to enter the country was launched by Tory MPs Duncan Sandys and Enoch Powell. Sandys had already told the Conservative Party Conference in 1967:

We are determined to preserve the British character of Britain. We welcome other races, in reasonable numbers. But we have already admitted more than we can absorb.[13]

Now Powell set about raising the temperature: he used deliberately provocative and racist language. He claimed a woman had written to him (anonymously, Powell alleged, out of fear of reprisals if her identity became known) claiming abuse by “Negroes”. She had, according to Powell’s story, paid off her mortgage and had started to let some of the rooms in her house to tenants; but she wouldn’t let to “Negroes”:

Then the immigrants moved in [to the neighbourhood]. With growing fear, she saw one house after another taken over. The quiet street became a place of noise and confusion. Regretfully, her white tenants moved out … She finds excreta pushed through her letter box. When she goes to the shops, she is followed by children, charming, wide-grinning piccaninnies.”[14]

Powell declared:

Those whom the gods wish to destroy, they first make mad. We must be mad, literally mad, as a nation to be permitting the annual inflow of some 50,000 dependants, who are for the most part the material of the future growth of the immigrant-descended population. It is like watching a nation busily engaged in heaping up its own funeral pyre.[15]

The British Empire, which Powell had supported, was no more. Its former subjects had fought for, and won, their independence. Satnam Virdee argues that, for Powell,

Black and Asian workers had now become the unintended reminder of peoples abroad who wanted nothing to do with the British Empire. And, in the mind of Powell, this invited the question, “What are they doing here in Britain?”[16]

For Powell, they “represented the living embodiment of the Empire that now was lost, a painful and daily reminder of [Britain’s] defeat on the world stage.”[17] For that reason, as well as his nightmare that the “immigrant-descended population” would lead to a “funeral pyre”, he was in favour of their repatriation (or, as he put it, their “re-emigration”) to the countries they or their parents had come from:

I turn to re-emigration. If all immigration ended tomorrow, the rate of growth of the immigrant and immigrant-descended population would be substantially reduced, but the prospective size of this element in the population would still leave the basic character of the national danger unaffected.[18]

The way to solve this problem was through “the encouragement of re-emigration”. Powell noted that no such policy had been tried, so there was no evidence from which to judge potential success or failure: “Nobody knows,” he said. So he once again called his constituents in aid to support him:

I can only say that, even at present, immigrants in my own constituency from time to time come to me, asking if I can find them assistance to return home. If such a policy were adopted and pursued with the determination which the gravity of the alternative justifies, the resultant outflow could appreciably alter the prospects.[19]

The leader of the Tory opposition, Edward Heath, sacked Powell from the shadow cabinet after the speech. But there were demonstrations in support of Powell in the immediate aftermath of the speech and his sacking. There were strikes by thousands of workers. They began in the West Midlands, where Powell’s constituency was located. Construction workers and power workers struck in Wolverhampton and Birmingham, there were strikes in Coventry and Gateshead. Then they spread to the London docks and the meat porters of Smithfield market. Strikers marched “from the East End to Westminster carrying placards reading ‘Don’t knock Enoch’ and ‘Back Britain, not Black Britain’.”[20]

But Powell remained sacked. His intervention was not welcomed by mainstream politicians in the Tory party, Labour or the Liberal Party. For one thing, his provocative racism seemed likely to threaten Britain’s social stability if unchecked. Moreover, good relations with the independent countries of the Commonwealth were still deemed vital to British interests: Powell’s racism not only threatened stability at home, it endangered good and profitable relations abroad. Nevertheless, there were some in official circles who seemed to believe that government promises to its citizens could be broken with impunity. Eric Norris, the British High Commissioner in Nairobi, was against allowing the Kenyan Asians in and he watched them as they queued outside his office demanding that the British government keep its promises and honour its commitments: “They all had a touching faith”, he later said scornfully, “that we’d honour the passports that they’d got.”[21] There had been still other pressures on the government: the far-right National Front – whose preoccupations were, like Powell’s, with white British identity and the repatriation of black and Asian immigrants – were stirring in the same pot. But the government could have resisted these pressures. The liberal press, churches, students and others opposed the campaign against the Kenyan Asians and could have been called in aid. Instead, it joined the Tory racists. Home Secretary James Callaghan wrote a memo to the cabinet:

We must bear in mind that the problem is potentially much wider than East Africa. There are another one and a quarter million people not subject to our immigration control … At some future time we may be faced with an influx from Aden or Malaysia.[22]

The Act was passed in 72 hours. It met Callaghan’s wider fears, and it rendered the Kenyan Asians’ passports worthless. No wonder that a year later The Economist declared that Labour had “pinched the Tories’ white trousers”.[23]

[1] By Hook or by Crook – Determined to be Hostile: https://bobmouncer.blog/2025/05/04/__trashed-2/

[2] Connell, Kieran (2024), Multicultural Britain: A People’s History, C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd., London, p. 46.

[3] Cited, ibid., p. 20.

[4] Cited, Malik, Kenan (1996), The Meaning of Race: Race, History and Culture in Western Society, Macmillan, Basingstoke, p. 19.

[5] Cited, ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Carter, B., Harris, C. & Joshi, S. (1993), “The 1951-55 Conservative Government and the Racialization of Black Immigration”, in James, W. & Harris, C. (eds), Inside Babylon: the Caribbean Diaspora in Britain, Verso, London, p. 65.

[8] Spencer, I. (1997), British Immigration Policy since 1939: the Making of Multi-Racial Britain, Routledge, London, p. 64.

[9] Hayter, T. (2000), Open Borders: the Case against Immigration Controls, Pluto Press, London, p. 44.

[10] Foot, P. (1968), The Politics of Harold Wilson, Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, p. 251.

[11] “Callaghan: I was wrong on police and race”, BBC News, 8 January 1999: BBC NEWS | Special Report | 1999 | 01/99 | 1968 Secret History | Callaghan: I was wrong on police and race

[12] Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1968, s. 1 (2A).

[13] Playing the Race Card, 24 October 1999, Channel Four Television, London.

[14] Palash Ghosh, ”Enoch Powell’s ’Rivers of Blood‘ Speech”, International Business Times, 14/6/2011: Enoch Powell’s “Rivers of Blood” Speech (FULL-TEXT) | IBTimes

[15] Ibid.

[16] Virdee, S. & McGeever, B. (2023). Britain in Fragments: Why things are falling apart, Manchester University Press, Manchester, p. 71.

[17] Ghosh, op cit.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Virdee, S. & McGeever, B. (2023). Britain in Fragments: Why things are falling apart, Manchester University Press, Manchester, pp., 72-74.

[21] Playing the Race Card, 24 October 1999, Channel Four Television, London.

[22] Cited, Hayter, T. (2000), Open Borders: the case against immigration controls, Pluto Press, London, p. 53.

[23] Cited, ibid., p. 51.

The hostile environment: Labour’s response

In the first blog in this series (https://bobmouncer.blog/2025/03/22/hostile-environment-the-windrush-scandal-i/), I showed how the announcement of a “hostile environment” for migrants by UK Home Secretary Theresa May in 2012 led to suffering and trauma for thousands of people, the Windrush generation. In the second blog (https://bobmouncer.blog/2025/03/26/hostile-environment-the-windrush-scandal-ii/), I told the story of Hubert Howard, who was one of its victims. In the third blog (https://bobmouncer.blog/2025/03/30/hostile-environment-the-windrush-scandal-iii/), I showed how documents that could have prevented the disaster to Hubert and thousands of others were deliberately destroyed; I described how the scandal slowly emerged and the government’s obstinate refusal to roll back on the policy; and I showed how a compensation scheme was finally devised and how it failed so many Windrush victims. In the last blog (https://bobmouncer.blog/2025/04/02/hostile-environment-the-mediterranean-scandal/) I described the Mediterranean scandal, in which the EU, including the UK, stopped rescue operations in the Mediterranean and how a UK government tried to deny its responsibility for the ensuing tragedy.

In this blog, I examine Labour’s response to the hostile environment.

Labour’s response

The two major scandals examined in my previous blogs in this series unfolded, first, under a Tory/LibDem coalition government and then under the subsequent Tory government. But what was Labour’s response to May’s hostile environment? Maya Goodfellow describes it as “the most minimal resistance”.[1] Labour, the official opposition, abstained in the final Commons vote on the Immigration Bill. Sixteen MPs voted against it, but only six of them were Labour MPs: Diane Abbott, Kelvin Hopkins, John McDonnell, Fiona Mactaggart, Dennis Skinner and Jeremy Corbyn. Corbyn said the Bill was

dog-whistle politics, the mantras being that every immigrant is an illegal immigrant who must somehow be condemned, and that immigration is the cause of all the problems in our society … If we descend into a UKIP-generated xenophobic campaign, it weakens and demeans all of us and our society, and we are all the losers for that.[2]

One of the other MPs was Sarah Teather, a LibDem MP and former minister, who had told The Guardian in 2013 that the proposals in the Bill were “hewn from the same rock” as earlier welfare cuts, much of which were “about setting up political dividing lines, and trying to create and define an enemy”.[3] But apart from the six rebels, Labour MPs obeyed their leader, Ed Miliband, and the Labour whips, and abstained in the Commons vote.

By October, Miliband had moved further right. In a by-election campaign in the Rochester and Strood constituency, which UKIP was hoping to win, Miliband declared he would toughen immigration policy if Labour won the general election in May the following year.[4] Echoing Theresa May, he raised familiar spectres and fears about immigration, ignoring its advantages. The UK, he said, “needs stronger controls on people coming here” and promised a new immigration reform Act if he became Prime Minister. His message was:

- If your fear is uncontrolled numbers of illegal migrants entering the country, Labour will crack down on illegal immigration by electronically recording and checking every migrant arrive in or depart from Britain

- If your fear is of widespread migrant benefit fraud, Labour will make sure that benefits are linked more closely to workers’ contributions

- If the spectre that haunts you is, as Margaret Thatcher had put it, that immigrants were bringing an “alien culture” to Britain, Labour understands, and will ensure that migrants integrate “more fully” into society

- Miliband turned his attention to the EU. Arguments about Britain’s EU membership were coming to a head at this time, with both the Tory right and UKIP agitating for the UK to leave. In 2013, Prime Minister David Cameron had agreed to renegotiate Britain’s terms of membership. The renegotiation would be followed by an in/out referendum to take place after the 2015 general election. Miliband, in his by-election speech in 2014, included migration from the EU in his new immigration promises. He claimed that Labour under Tony Blair had wrongly opened the UK to Eastern Europeans when their countries had joined the EU in 2004. He would not let that happen again. If he won the 2015 election, there would be longer “transitional controls” for new EU members before they could move to Britain.

He even told the voters of Rochester and Strood that they didn’t need to vote for UKIP to get these policies: Labour would do the job.

One pledge seemed at first sight to be protective of migrants. Miliband said he wanted to ensure that migrants were not exploited by employers. However, this was, in fact, a reference to another fear – that migrant workers undercut native workers’ wages because bosses often pay lower wages to migrants (often below the minimum wage). However, where this problem exists, its solution lies not in immigration law but in employment law and its enforcement. It also lies in union recognition and legally binding agreements.

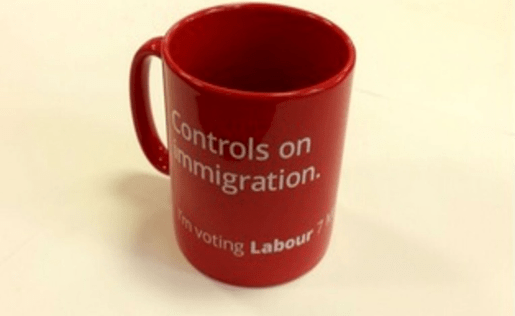

As promise followed promise and pledge followed pledge, Miliband began to sound like Theresa May. A few months later, as the 2015 election approached, Labour’s campaign included the issuing of mugs with “Controls on immigration” printed on them.

Labour’s immigration controls mug

None of this saved Miliband or his party, and the Tories won the 2015 election; the referendum vote in 2016 in favour of leaving the EU led to David Cameron’s resignation as Prime Minister; he was succeeded by Theresa May; Ed Miliband resigned as Labour leader; Jeremy Corbyn was elected in his place; the process of leaving the EU began. In 2017, Theresa May called another general election, hoping to increase her majority. In the event, the Tory party lost its small overall majority but won the election as the largest single party. But from then on it had to rely on Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) votes to get its business through the Commons.

These parliamentary changes meant nothing for the Windrush generation. The scandal began to come to light in 2017 but their suffering continued beyond the end of the decade, one of the main reasons being that the compensation scheme was seriously flawed. This remained a problem in April 2025, almost a year after the election of a Labour government. The Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman (PHSO), Rebecca Hilsenrath, had found that

further harm and injustice are still being caused by failings in the way the scheme is working. We found recurrent reasons for this, suggesting these were not one-off issues but systemic problems.[5]

In response, the Home Office sought to give some reassurance:

This government is committed to putting right the appalling injustices caused by the Windrush scandal and making sure those affected receive the compensation they rightly deserve.[6]

Nevertheless, given the Home Office’s record, we should hesitate before we are reassured. In 2020, the Williams review of the Windrush scandal had made 30 recommendations to the government, all of which were accepted by Priti Patel, Tory Home Secretary at the time. In January 2023, the Home Office unlawfully dropped three of them.[7] Moreover, the department prevented the publication of a report prepared in response to the Williams Review. Williams had said that Home Office staff needed to “learn about the history of the UK and its relationship with the rest of the world, including Britain’s colonial history, the history of inward and outward migration and the history of black Britons.” As a result, the Home Office commissioned an independent report: The Historical Roots of the Windrush Scandal. In the words of Jim Dunton, the report

lays much of the blame for the Windrush scandal on essentially racist measures introduced to restrict the ability of Commonwealth citizens to move to the UK in the years since the second world war.[8]

The report has been available internally since 2022 but, writes Dunton, “the department resisted attempts for it to be made publicly available, including rejecting repeated Freedom of Information Act requests and pressure from Labour MP Diane Abbott.” Then, in early September 2024, after a legal challenge was launched,

a First Tier Tribunal judge ordered the document’s publication, quoting George Orwell’s memorable lines from 1984: “Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past.”[9]

So the Home Office, reluctantly, made the report publicly available, and I will refer to its findings in future blogs. But it is not yet time to take Home Office reassurances at face value. Or Labour’s reassurances, come to that.

In future blogs: more on Labour’s record on immigration and race; and the necessary exposure of a long-standing myth.

[1] Goodfellow, M. (2019), Hostile Environment: How immigrants became Scapegoats, Verso Books, London, loc. 167.

[2] Jack Peat, “Just 6 Labour MPs voted against the 2014 Immigration Act”, The London Economic, 19/04/2018:

[3] Decca Aitkenhead, “Sarah Teather: ‘I’m angry there are no alternative voices on immigration’.”, The Guardian, 12 July 2013.

[4] Andrew Grice, “Ed Miliband attempts to take on Ukip – with toughened immigration policies”, The Guardian, 24 October 2014: Ed Miliband attempts to take on Ukip – with toughened immigration policies | The Independent | The Independent

[5] Adina Campbell, “Payments for Windrush victims denied compensation”, BBC News, 5 September 2024: Payments for Windrush victims denied Home Office compensation – BBC News

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ashith Nagesh & André Rhoden-Paul, “Home Office unlawfully axed Windrush measures”, BBC News, 19 June 2024: Windrush Scandal: Home office unlawfully axed recommendations, court rules – BBC News

[8] Jim Dunton, “Home Office publishes internal ‘roots of Windrush’ report after FoI battle”, Civil Service World, 27 September 2024: Home Office publishes internal ‘roots of Windrush’ report after FoI battle

[9] Ibid.

Uncomfortable history

Introduction

Here’s something that has been nagging at me for some time. During my PhD research, I found that the usual narrative told about post-war Britain (that we welcomed the Windrush generation and other Commonwealth citizens with open arms when they came to help rebuild the country after the Second World War) was far from the truth. In fact, active attempts were made during that time, first to avoid asking black and Asian migrants to come here, then to try to discourage them from coming, then to find arguments to justify a law preventing them from coming. Such arguments were found, spurious as they were, and an Act was passed. All that was shocking to me. But I have also realised for some time that pretty much nobody ever tells that story. It’s the old, comforting story that gets told.

So I want to tell the uncomfortable story again, and in a bit more detail. Because this is a time when we are learning that Black Lives Matter. We are being reminded that structural and institutional racism exists here as much as in the US, with some of the consequences of that being persistent inequality and poverty, the ongoing Windrush generation scandal (during which the comforting version of history has been repeated ad nauseam), the long list of BAME people who have died at the hands of the police and the disproportionate effect of covid-19 on BAME people, and much more besides. At a time when white society is facing demands from BAME communities to tell the history between us the way it is, I don’t think we should be telling comforting stories about our past and complacent stories about our present. Nothing will change if we do that. So here it is. My contribution to one bit of our history.

Post-war reconstruction

The task of reconstruction in the UK after the Second World War was massive and daunting: many workers had been killed in the fighting and much of the country‘s infrastructure and industry had been destroyed in the bombing. Moreover, the government was committed to social change, for the people had demanded not just victory but a better world. The politicians remembered how the First World War had been followed by the Russian Revolution and Quintin Hogg (later Lord Hailsham) warned the House of Commons in 1943 that “if you do not give the people social reform, they are going to give you social revolution”.[1] As Hobsbawm notes:

Nobody dreamed of a post-war return to 1939 … as statesmen after the First World War had dreamed of a return to the world of 1913. A British government under Winston Churchill committed itself, in the midst of a desperate war, to a comprehensive welfare state and full employment.[2]

Civis Britannicus sum

Such a project would require much work and many workers, and the story of how the job was eventually done is usually told in terms of the willing recruitment of black and Asian workers from the colonies and ex-colonies to augment the labour force. As more and more colonies achieved independence, imperial rhetoric about British rule over an empire “on which the sun never sets” gave way to a Commonwealth rhetoric used by both Labour and Conservative parties for many years following the war. Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell told his party conference in 1961:

I believe with all my heart that the existence of this remarkable, multiracial collection – association – of independent nations, stretching across five continents, covering every race, is something that is potentially of immense value to the world.[3]

More specifically, in 1954, Henry Hopkinson, Conservative minister of state at the Colonial Office, declared that colonial subjects’ right of free entry into the UK was

not something we want to tamper with lightly … We still take pride in the fact that a man can say civis Britannicus sum [I am a British citizen] whatever his colour may be and we take pride in the fact that he wants to and can come to the mother country.[4]

Indeed, for at least a century no distinction had been made between citizens of the British Empire regarding their right to enter Britain. The reasons for this were economic and political: from the middle of the nineteenth century “the economic imperatives of the free flow of goods, labour and services within the Empire enhanced the feeling that such distinctions were likely to be detrimental to broad imperial interests”.[5] In the post-war period Britain wanted to foster good relations with the newly independent countries in order to keep a foothold, particularly in terms of economic power, in the regions of the world it once ruled. These were the realities which underlay the softer talk of the Commonwealth and the continued right of free entry into Britain for all its members – and it was against this background that the British Nationality Act 1948 was introduced. It defined UK and Colonies citizenship. But for most politicians this meant “the continued flow of two-way traffic between Britain and the ‘old dominions’ – Canada, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand – which were sometimes called the ‘white dominions’ or the ‘old commonwealth’.”[6] David Olusoga explains:

The Act was intended to ensure that British people remained free to settle in the colonies and commonwealth citizens were free to reside in Britain. The people the government envisaged making use of the rights of entry and residence enshrined in the 1948 Act were white people of “British stock” … who were coming “home” to Britain.[7]

Two-way traffic? Of course: “Most of the 720,000 Britons who left their war-ravaged homeland between 1946 and 1950 headed for new lives in the old dominions.”[8] Inevitably, however, the Act also confirmed rights of entry for all Commonwealth citizens, which turned out to be exactly what the post-war Labour government didn’t want.

“… we cannot force them to return …”

The 1945 Labour government attempted from the beginning to limit the number of black and Asian Commonwealth and colonial citizens allowed into the country. It resorted to administrative methods of control, many of doubtful legality and most of them secret. The government’s first action was to ensure the early repatriation of the black workers who had been urgently recruited from the colonies during the war. It also set about discouraging them from returning. This was true in the case of about a thousand Caribbean technicians and trainees recruited to work in war factories in Merseyside and Lancashire. In April 1945 an official at the Colonial Office had minuted that, because they were British subjects, “we cannot force them to return” – but it would be “undesirable” to encourage them to stay.[9] The Ministry of Labour managed to repatriate most of them by the middle of 1947. Then, in order to discourage them from returning, an official film was distributed in the Caribbean

showing the very worst aspects of life in Britain in deep mid-winter. Immigrants were portrayed as likely to be without work and comfortable accommodation against a background of weather that must have been filmed during the appallingly cold winter of 1947-8.[10]

Nevertheless, on 22 June 1948, 492 passengers disembarked from the Empire Windrush. They had travelled on the ship from the West Indies. While the London Evening Standard (with the headline, “Welcome Home”) and a film crew from Pathé News seemed pleased, the government was not. Minister of Labour George Isaacs “was quick to stress that the West Indians had not been officially invited to Britain”, writes Olusoga.[11] Isaacs warned his colleagues of “considerable difficulty and disappointment” to come and he expressed the hope that “no encouragement will be given to others to follow their example”. Attlee himself had tried to get the Empire Windrush “diverted to East Africa, and the West Indian migrants offered work on groundnut farming projects there”.[12] No chance. They were British subjects, and to Britain they came.

Redistribution of labour and recruitment from Europe

Whatever Attlee and Isaacs may have wanted, the need for labour remained and the government tried to solve the problem in two ways – neither of which involved importing Commonwealth labour. First, it tried to increase labour mobility within the existing population and, secondly, it imported labour from Europe. A Ministry of Labour report had predicted before the end of the war that there would not be sufficient mobility of labour within the country to face the challenges of the post-war world.[13] Workers would have to be more willing to move into sectors where they were needed most. Virtually no one could be excluded, for everyone had to be part of the reconstruction project, even the unskilled and those “below normal standards”.[14] In 1947 the government issued an invitation for people to go to their local labour exchanges to register. Some incentives (in the form of Ministry of Labour hostels and training) were provided, plus the threat of prosecution.[15] The presenter of the radio programme Can I Help You? entered into the spirit of the government’s intentions: “The hope is … to comb out from plainly unessential [sic] occupations people who could be better employed; and to get the genuine drones in all classes to earn their keep …”[16]

Attlee had hoped that this project would provide what he had identified as the “missing million” workers[17] but six months later only 95,900 of the “drones” had responded.[18] Moreover, one source of home-grown labour had hardly been tapped in this exercise: women, essential workers during the war, were now told to go back to the home and make way for the men returned from battle. There were still sectors where women might work (e.g. textiles) but, as Harris notes, “their ability to do so was greatly hampered by the reluctance of the government to maintain the war-time level of crèche provision.”[19] Thus an important source of labour was largely excluded.

In the case of immigration from Europe, the government set up Operation Westward Ho in 1947 in order to recruit labour from four sources: Poles in camps throughout the UK; displaced persons in Germany, Austria and Italy; people from the Baltic states; and the unemployed of Europe.[20] It was partly knowledge of this recruitment which inspired pleas to the British government from the governors of Barbados, British Guiana, Trinidad and Jamaica. Each of these territories was suffering from high unemployment, with consequent discontent among their populations, and the governors wrote to London arguing that Britain could solve its own problem and theirs by accepting these workers into the UK. In response to this, an interdepartmental working party was set up which decided that there was no overall shortage of labour after all.[21] The working party’s minutes also display “entirely negative attitudes to colonial labour”:

One senior official at the Ministry of Labour expressed the view that the type of labour available from the empire was not suitable for use in Britain and that displaced persons from Europe were preferable because they could be selected for their specific skills and returned to their homes when no longer required. Colonial workers were, in his view, both difficult to control and likely to be the cause of social problems.[22]

“… the object is to keep out coloured people”

Opposition to black and Asian immigration continued throughout the next decade, with successive British governments seeking to justify legislation to control it. Hayter observes that the delay in introducing the legislation “was caused by the difficulty of doing so without giving the appearance of discrimination”.[23] There is no doubt, however, about the racist nature of the intent to do so. From 1948 onwards various working parties and departmental and interdepartmental committees were set up to report on the “problems” of accepting black immigrant workers into the UK. All of them were created in the hope of providing evidence that black immigrants were bad for Britain. There was the “Interdepartmental Working Party on the employment in the United Kingdom of surplus colonial labour”, chaired by the Colonial Office; the Home Office based “Interdepartmental Committee on colonial people in the United Kingdom”; the “Cabinet Committee on colonial immigrants”; and the one that really gave the game away: the “Interdepartmental Working Party on the social and economic problems arising from the growing influx into the United Kingdom of coloured workers from other Commonwealth countries”.

Committees reported, cabinets discussed their findings and much correspondence passed between ministers and departments. Lord Salisbury (Lord President of the Council and Leader of the House of Lords) wrote in March 1954: “It is not for me merely a question of whether criminal negroes should be allowed in … it is a question of whether great quantities of negroes, criminal or not, should be allowed to come.”[24] Lord Swinton, secretary of state for Commonwealth relations, saw a difficulty and wrote to Salisbury: “If we legislate on immigration, though we can draft it in non-discriminatory terms, we cannot conceal the obvious fact that the object is to keep out coloured people.”[25] In the case of the “old Dominions” (i.e. the “white” Commonwealth), he noted a “continuous stream” of people coming to the UK “in order to try their luck; and it would be a great pity to interfere with this freedom of movement.”[26] Moreover, such interference would undermine the strong ties of kith and kin between the UK and the “white” Commonwealth. Swinton also believed that those strong ties would be further weakened by the development of a large “coloured” community in Britain – declaring that “such a community is certainly no part of the concept of England or Britain to which people of British stock throughout the Commonwealth are attached.”[27] “Swinton held the view strongly”, writes Spencer, “that immigration legislation which adversely affected the rights of British subjects should be avoided if humanly possible, and if it did become inevitable it was better for the legislation to be overtly discriminatory than to stand in the way of all Commonwealth citizens who wished to come to Britain.”[28]

Obstacles to racist controls

The Commonwealth connection

It was not just concern for the “white” Commonwealth which made governments delay legislating for controls until 1961. The UK’s relationship with the Commonwealth as a whole was also a factor. In a period of decolonisation and the building of Commonwealth institutions, UK governments trod carefully. For example, openly discriminatory legislation “would jeopardise the future association of the proposed Federation of the West Indies with the Commonwealth.”[29] Politicians tried to persuade governments in the Caribbean and the Indian subcontinent to control the flow of migrants at source. They had some success in India and Pakistan, but not in the Caribbean. In 1958 Sir Henry Lintott, Deputy Under-Secretary of State at the Commonwealth Relations Office, advised caution on the question of legislation. There had been calls for immigration controls in the wake of the Notting Hill riots (provoked by extreme right-wing groups). Sir Henry advised that in these circumstances immigration controls would imply that “the British people are unable to live with coloured people on tolerable terms”:

This could be immensely damaging to our whole position as leaders of the Commonwealth which, in its modern form, largely draws its strength from its multi-racial character. If, therefore, strong pressure develops for the introduction of legislation to control immigration, I would hope that some way could be found to delay action and to permit passions to cool.[30]

These arguments were supported by many in the Conservative Party in the mid-1950s and by the Labour Party too. In 1958 Arthur Bottomley spoke for the Labour front bench against legislation to control immigration:

The central principle on which our status in the Commonwealth is largely dependent is the “open door” to all Commonwealth citizens. If we believe in the importance of our great Commonwealth, we should do nothing in the slightest degree to undermine that principle.[31]

With a House of Commons majority of only fifteen, the Conservative government was vulnerable. Similar considerations had applied in January 1955 when Home Secretary Gwilym Lloyd George presented his ideas for restrictive legislation to the cabinet. The cabinet judged that “such a bill would not obtain the full support of the Conservative Party and would be opposed in the House by the Labour opposition and outside the House by the Trades Union Congress.”[32]

The working party evidence

Another obstacle to immediate legislation was the fact that the working parties set up to provide evidence of the “undesirability” of black immigrants failed to do so. They described “coloured women” as “slow mentally” and said that their “speed of work” was unsatisfactory. They claimed there was “a disproportionate number of convictions for brothel keeping and living on immoral earnings” among West Indian men and made references to “the incidence of venereal disease among coloured people”.[33] But they failed to make the case for immigration legislation. The committee with the specific mandate to investigate “social and economic problems” relating to “coloured workers” must have been a particular disappointment. In August 1955 the committee’s draft statement went to the cabinet. The allegation of a high incidence of venereal disease was included here – but only as a “suggestion”. The author of the report admitted that there were no figures to support the claim.[34] Spencer summarises the committee’s findings:

Although “coloured” immigration was running at the rate of about 30,000 a year … even those arriving most recently had found jobs easily and were making “a useful contribution to our manpower resources”. Unemployment … could not be regarded as a problem, nor could undue demands on National Assistance or the National Health Service … The immigrants were for the most part law-abiding except for problems with [cannabis] and living off the immoral earnings of women. Though the immigrants had not been “assimilated” there was no evidence of racial tension and it was apparent that some “coloured” workers in the transport industry had made a favourable impression.[35]

The same was true of the working party’s reports between 1959 and 1961. “Viewed objectively”, writes Spencer, “the reports of the Working Party consistently failed to fulfil the purpose defined in its title – to identify ‘the social and economic problems arising from the growing influx of coloured workers’. In the areas of public order, crime, employment and health there was little noteworthy to report to their political masters.”[36] Moreover, the Treasury, when asked whether black and Asian immigration benefited the economy, “gave the clear advice that on economic grounds there was no justification for introducing immigration controls: most immigrants found employment without creating unemployment for the natives and, in particular, by easing labour bottlenecks, they contributed to the productive capacity of the economy as a whole.”[37] But, in the end, the working party managed to construct an argument for controls: “‘Assimilability’ – that is, of numbers and colour – was the criterion that mattered in the end.”[38] Between 1959 and 1961 there were large increases in the numbers of blacks and Asians entering the UK. At the beginning of the period there were around 21,000 entries a year; by the end they had risen to 136,000 (though much of this last figure may have been due to the fact that the government had signalled its intention to introduce legislation and larger numbers had decided to come in order to “beat the ban”). Working party officials compensated for their inability to find existing problems by predicting that they would arise later:

Thus in February 1961, whilst it was admitted that black immigrants were being readily absorbed into the economy, [officials predicted] “it is likely to be increasingly difficult for them to find jobs during the next few years”. Further, it was doubtful if the “tolerance of the white people for the coloured would survive the test of competition for employment”.[39]

There would be “strains imposed by coloured immigrants on the housing resources of certain local authorities and the dangers of social tensions inherent in the existence of large unassimilated coloured communities.”[40] The working party recommended immigration controls. It was “prepared to admit that the case for restriction could not ‘at present’ rest on health, crime, public order or employment grounds”, writes Spencer, but

[i]n the end, the official mind made recommendations based on predictions about … future difficulties which were founded on prejudice rather than on evidence derived from the history of the Asian and black presence in Britain.[41]

Now there was just one obstacle impeding the introduction of controls.

Public opinion

One of the government’s worries about introducing legislation had been the uncertainty of public opinion. Racist stereotyping in the higher echelons of government could also be found among the general population. Bruce Paice (head of immigration, Home Office, 1955-1966), interviewed in 1999, believed that “the population of this country was in favour of the British Empire as long as it stayed where it was: they didn‘t want it here.”[42] It is true that hostility towards black people existed throughout the 1950s, and in 1958 the tensions turned into violent confrontation. In Nottingham and in the Notting Hill area of London there were attacks on black people, followed by riots, orchestrated by white extremist groups.[43] After these explosions, racist violence continued but became more sporadic, ranging from individual attacks to mob violence.[44] Nevertheless, for much of this period governments had not been confident that public opinion would be on its side when it came to legislation on immigration control. In November 1954 the colonial secretary wrote a memorandum expressing the hope that “responsible public opinion is moving in the direction of favouring immigration control”. There was, however, “a good deal to be done before it is more solidly in favour of it”.[45] In June 1955 cabinet secretary Sir Norman Brook wrote to prime minister Anthony Eden expressing the view that, evident as the need was for controls, the government needed “to enlist a sufficient body of public support for the legislation that would be needed.”[46] In November 1955 the cabinet recognised that public opinion had not “matured sufficiently” and public consent “could only be assured if the racist intent of the bill were concealed behind a cloak of universalism which applied restrictions equally to all British subjects.”[47]

Mission accomplished

By 1961 the cloak was in place, and a Bill could be prepared. Home secretary R.A. Butler donned the cloak in a television interview: “We shall decide on a basis absolutely regardless of colour and without prejudice,” he told the interviewer. “It will have to be for Commonwealth immigration as a whole if we decide [to do it].”[48] He removed the cloak, however, when he explained the work-voucher scheme at the heart of the Bill to his cabinet colleagues:

The great merit of this scheme is that it can be presented as making no distinction on grounds of race or colour … Although the scheme purports to relate solely to employment and to be non-discriminatory, the aim is primarily social and its restrictive effect is intended to, and would in fact, operate on coloured people almost exclusively.[49]

The Bill passed into law and became the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962. Though Gaitskell’s Labour Party had strongly campaigned against it, and voted against it in parliament, the 1964 Labour government under Harold Wilson increased the immigration controls. The 1962 Act was the first of many post-war Acts, Orders, Statutory Instruments and Regulations that deny people rights, status, equality, honour and respect, and they culminate in the latest Immigration and Social Security Bill going through parliament at the moment. This is a history in which both Conservative and Labour governments are implicated. Nobody has clean hands.

[1] Philo, G. (undated), Television, Politics and the New Right, p. 2, Glasgow University Media Group. Available from http://www.gla.ac.uk/centres/mediagroup

[2] Hobsbawm, E. (1995), Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century, 1914-1991, p. 161, Abacus, London.

[3] Race Card: Playing the Race Card, 24 October 1999, Channel Four Television, London.

[4] Hayter, T. (2000), Open Borders: the Case against Immigration Controls, p. 44, Pluto Press, London.

[5] Spencer, I. (1997), British Immigration Policy since 1939: The Making of Multi-Racial Britain, p. 53, Routledge, London.

[6] Olusoga, D. (2017), Black and British: A Forgotten History, chapter 14, Kindle edition, Pan Books, London.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Cited, Spencer, I. (1997), British Immigration Policy since 1939: The Making of Multi-Racial Britain, p. 39, Routledge, London.

[10] Ibid., p. 32.

[11] Cited, Olusoga, D. (2017), Black and British: A Forgotten History, chapter 14, Kindle edition, Pan Books, London.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Harris, C. (1993), “Post-war Migration and the Industrial Reserve Army”, in James, W. & Harris, C. (eds), Inside Babylon: the Caribbean Diaspora in Britain, p. 16, Verso, London.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid., pp. 18-19.

[16] Ibid., p. 17.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid., pp. 17-18.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid., p. 19.

[21] Spencer, I. (1997), British Immigration Policy since 1939: The Making of Multi-Racial Britain, p. 40, Routledge, London.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Hayter, T. (2000), Open Borders: the Case against Immigration Controls, p. 46, Pluto Press, London.

[24] Carter, B., Harris, C. & Joshi, S. (1993), “The 1951-55 Conservative Government and the Racialization of Black Immigration”, in James, W. & Harris, C. (eds), Inside Babylon: the Caribbean Diaspora in Britain, p. 65, Verso, London.

[25] Spencer, I. (1997), British Immigration Policy since 1939: The Making of Multi-Racial Britain, p. 64, Routledge, London.

[26] Ibid., p. 67.

[27] Ibid., pp. 67-68.

[28] Ibid., p. 68.

[29] Ibid., p. 82.

[30] Ibid., p. 102.

[31] Cited, Foot, P. (1968), The Politics of Harold Wilson, p. 251, Penguin Books, Harmondsworth.

[32] Spencer, I. (1997), British Immigration Policy since 1939: The Making of Multi-Racial Britain, p. 76, Routledge, London.

[33] Race Card: Playing the Race Card, 24 October 1999, Channel Four Television, London.

[34] Spencer, I. (1997), British Immigration Policy since 1939: The Making of Multi-Racial Britain, p. 78, Routledge, London.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Ibid., p. 119.

[37] Hayter, T. (2000), Open Borders: The Case against Immigration Controls, p. 48, Pluto Press, London.

[38] Spencer, I. (1997), British Immigration Policy since 1939: The Making of Multi-Racial Britain, p. 118, Routledge, London.

[39] Ibid., p. 119.

[40] Ibid., p. 118.

[41] Ibid., p. 120.

[42] Race Card: Playing the Race Card, 24 October 1999, Channel Four Television, London.

[43] Favell, A. (2001), Philosophies of Integration: Immigration and the Idea of Citizenship in France and Britain, p. 103, Palgrave, Basingstoke.

[44] Fryer, P. (1984), Staying Power: the History of Black People in Britain, p. 380, Pluto Press, London.

[45] Carter, B., Harris, C. & Joshi, S. (1993), “The 1951-55 Conservative Government and the Racialization of Black Immigration”, in James, W. & Harris, C. (eds), Inside Babylon: the Caribbean Diaspora in Britain, p. 66, Verso, London.

[46] Cited, ibid.

[47] Ibid., p. 68.

[48] Race Card: Playing the Race Card, 24 October 1999, Channel Four Television, London.

[49] Cited, Hayter, T. (2000), Open Borders: The Case against Immigration Controls, p. 47, Pluto Press, London.

On shouting and voting

Calls to vote Labour in the Euro and local elections and, perhaps more particularly, in the 2015 general election, give rise to an awkward question for anti-racists. What would we be voting for? In a Channel 4 News interview on 14 May Krishnan Guru-Murthy pitted Chris Leslie (Labour’s Shadow Chief Secretary to the Treasury) against Nicky Morgan (Tory Financial Secretary to the Treasury). The first question was: “Is the current level of immigration good for the economy?” Chris Leslie said, “Yes, I think so” – but then went on to say no. “The key here”, he said,

“is [that] Nicky promised before the general election – I don’t think it was a wise thing for her to do, but she promised – that they would keep that net migration down below 100,000, and it looks as though the government have dropped that plan now.”

After a bit of “Oh no we haven’t” pantomime from Morgan, Leslie then admonishes her:

“You promised it would be all down. The thing is you shouldn’t make promises that you’re not going to keep. It’s really important.”

I immediately wanted to tell Krishnan to quote Labour’s Roy Hattersley (1999 version) at Leslie. Roy Hattersley (1965 version, when he was Home Office Minister) had argued for tightening immigration controls on the grounds that “Integration without control is impossible, but control without integration is indefensible.” This convenient little formula was too neat to be true. 34 years later he acknowledged his mistake and explained why he now thought he had been wrong:

“If your immigration restrictions are too repressive you encourage bad race relations rather than encourage contentment and satisfaction, because you are saying, ‘We can’t afford any more of these people here’, and the implication is that there is something undesirable about these people.”

This is true of immigration controls in general, of course, not just the oddly named “too repressive” ones! But in any case Krishnan couldn’t hear me shouting at the TV screen and Labour remains indistinguishable from the Tories.

Anyway, I’m going out to vote for somebody or another because I don’t want to see UKIP gain any ground at all.

“Liberal agenda” masks “political cowardice”

After donning the white trousers (see previous blog: https://bobmouncerblog.wordpress.com/2014/03/31/pinching-the-tories-white-trousers/ ) what did Labour do?

Race relations

After Labour’s tightening of immigration controls following the 1964 election, the rest of the 1960s saw the development of a new approach to race and immigration in the UK: the race-relations approach. This was tacitly supported by the Conservatives, who were also worried by the uncertain consequences of the racial hatred stirred up at Smethwick. Conservative frontbencher Robert Carr saw the consensus between the two parties as “a marriage … of convenience – not from the heart.”[1] Labour insisted that its liberal credentials were intact because the approach’s emphasis on integration was the key to social peace, the mark of a “civilised society”. But (crucially, and to justify the tightening-up of the Act) it would have to include immigration controls if it was to be successful. In 1965 Home Office minister Roy Hattersley expressed it thus: “Integration without control is impossible, but control without integration is indefensible.”[2] When Roy Jenkins became home secretary in 1966 he laid out his policy stall in a speech which was to become a foundation text for the new approach. He emphasised the integration side of Hattersley’s equation, defining it both negatively and positively:

“I do not regard [integration] as meaning the loss, by immigrants, of their own national characteristics and culture. I do not think we need in this country a “melting pot”, which will turn everyone out in a common mould, as one of a series of carbon copies of someone’s misplaced vision of the stereotyped Englishman.”[3]

He defined integration positively as “cultural diversity, coupled with equality of opportunity in an atmosphere of mutual tolerance”, and added: “If we are to maintain any sort of world reputation for civilised living and social cohesion, we must get far nearer to its achievement than is the case today.” Here was the moral, political and social justification for his liberal agenda and the multicultural society that would evolve from it.

Contradiction

There was, however, a contradiction at the heart of the approach which has dogged it ever since: it is inconsistent to claim to want to celebrate cultural diversity in society on the one hand and discriminate against black and Asian immigrants on the other. Thirty-four years later Roy Hattersley admitted as much: “If your immigration restrictions are too repressive you encourage bad race relations rather than encourage contentment and satisfaction, because you are saying, ‘We can’t afford any more of these people here’, and the implication is that there is something undesirable about these people.”[4] The truth is that race relations policy was not the result of high principle (as suggested by Gaitskell’s opposition to the 1962 Act or by Jenkins’s exposition of his liberal agenda) but of the complete abandonment of principle after 1964. After Smethwick “the government panicked”, explained Barbara Castle. The tightening-up of restrictions by Labour was done “out of political cowardice, not political conviction.”[5] So the whole liberal project had its origin in a surrender to racism.

A “half-hearted affair” for “a people apart”

This helps to explain the weakness of the first Race Relations Act in 1965 and the inadequacies of the second in 1968. The 1965 Act prohibited “incitement to racial hatred” but did not cover discrimination in housing and employment, did not contain criminal sanctions against those who discriminated, and did not apply to the police. A. Sivanandan, working at the Institute for Race Relations, described it as “a half-hearted affair which merely forbade discrimination in ‘places of public resort’ and, by default, encouraged discrimination in everything else: housing, employment, etc.”[6] Moreover, the Race Relations Board, set up under the Act to provide for a conciliation process to deal with discrimination in public places, sent the wrong message: “To ordinary blacks,” Sivanandan argued, such structures “were irrelevant: liaison and conciliation seemed to define them as a people apart who somehow needed to be fitted into the mainstream of British society – when all they were seeking was the same rights as other citizens.” The ineffectiveness both of the Act and the Board is summed up by Hayter:

“The first person to be charged under this Act was Michael X, a black militant. When Duncan Sandys, a prominent Tory MP, attacked a government report on education by stating that ‘The breeding of millions of half-caste children will merely produce a generation of misfits and increase social tension’, the Race Relations Board was unable or unwilling to prosecute him.”[7]

The 1968 Race Relations Act went further by bringing employment and housing into its ambit, but its inadequacies were apparent:

“The Act introduced fines on employers who were found to discriminate on the grounds of race, and compensation, but not reinstatement, for the people discriminated against … but the enforcement powers of the Race Relations Board remained weak.”[8]

Moreover, the anti-discrimination provisions still did not apply to the police. Jenkins had faced opposition from the police when discussing the first Act and in 1968 the new home secretary, James Callaghan, bowed to similar pressure. The year 1968 also saw the passing of another Commonwealth Immigrants Act.

In the next blog: the Kenyan Asians and Enoch Powell.

[1] Playing the Race Card, October-November 1999, Channel Four Television, London.

[2] Favell, A. (2001), Philosophies of Integration: Immigration and the Idea of Citizenship in France and Britain, Palgrave, Basingstoke, p. 104.

[3] Cited, ibid.

[4] Playing the Race Card, October-November 1999, Channel Four Television, London.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Cited, Fryer, P. (1984), Staying Power: the History of Black People in Britain, Pluto Press, London, p. 383.

[7] Hayter, T. (2000), Open Borders: the Case against Immigration Controls, Pluto Press, London, p. 35.

[8] Ibid.

Pinching the Tories’ white trousers

To continue the story from where the earlier blog left off, when the Bill to impose racist immigration controls became the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962.

Labour had opposed the Bill throughout its passage through parliament – largely because it regarded the Bill as incompatible with the Commonwealth ideal. Moreover, such principles were apparently non-negotiable: “I do not care whether or not fighting this Commonwealth Immigration Bill will lose me my seat”, declared MP Barbara Castle, “for I am sure that the Bill will lose this country the Commonwealth.”[1] The speech against the Bill by the Labour leader, Hugh Gaitskell, was admired even by some on the Conservative benches. Yet, once Labour had won the 1964 election, the new government set about making the Act even more restrictive.

Pressures

Why should this have been so? First, there was pressure on the government from Whitehall. Bruce Paice (head of immigration, Home Office, 1955-1966) had argued hard over the years for immigration controls. Even in retirement he was unable to conceal his contempt for the immigrants who came and the politicians and civil servants who allowed them to come for so long. “How on earth people got the money to come here from places like West Africa and Barbados I’ve no idea”, he said in 1999.[2] “They never seemed to earn anything when they were there, and most of them I think didn’t make much effort to earn anything much when they were here either.” He had tried to persuade senior officials that the solution was a simple one:

“I remember going to see Sir Arthur Hutchinson, Deputy Secretary, and I said all that was really needed was to give me the same powers about British subjects as I had about aliens. And he said in effect, ‘Oh, don’t be silly,’ he said, you know, there couldn’t be any question of such a thing.”

In 1962 Paice had his way: Commonwealth immigrants now had to queue with “aliens” for permission to enter. “The fact that I might be influencing, for good or ill, the lives of other people”, he later commented, “was to me just one of those things. It didn’t cost me any sleepless nights. Somebody has to do this kind of job, and I was quite happy to do it.”

Secondly, there was pressure from public opinion. When the debate on the Act began, support for immigration controls stood at 76%. But the Labour Party’s campaign against the Bill changed the situation: by the end of its passage through the House of Commons, support for controls had fallen to 62% (Jenkins 1999). It looked as though a strong campaign had changed people’s minds. Nevertheless a majority of 62% was still a majority – and Labour was starting to think about the next election. Even before the Bill was passed, there were signs that Labour’s commitment to the rights of free entry and settlement of Commonwealth citizens was less than firm. During the third reading of the Bill, Labour frontbencher Denis Healey hinted that controls might be necessary in the future.[3] After Gaitskell’s unexpected death the new leader, Harold Wilson, gave a further hint of change. While opposing the renewal of the Act in November 1963 he nevertheless told the House of Commons: “We do not contest the need for control of Commonwealth immigration into this country.”[4] When the election came in 1964 the Labour Party manifesto declared:

“Labour accepts that the number of immigrants entering the United Kingdom must be limited. Until a satisfactory agreement covering this can be negotiated with the Commonwealth, a Labour Government will retain immigration control.”[5]

Smethwick

If this was the case before the election, tighter controls became inevitable after it. Labour’s shadow foreign secretary, Patrick Gordon Walker, had lost his seat in Smethwick, in the West Midlands, to a Conservative, Peter Griffiths. One of the slogans daubed on walls during the campaign became notorious in British electoral history: “If you want a nigger for a neighbour, vote Labour.” Griffiths denied being the author, but added: “I would not blame anyone who said that … it was a manifestation of popular feeling.”[6] Smethwick, like many similar inner-city areas, suffered housing shortages and other problems, due not to immigrants but to policy failures both at national and local levels. But Griffiths blamed immigrants – and Gordon Walker blamed the Conservatives for letting so many into the country.[7] At an election meeting in Birmingham, Wilson did manage to identify the real issue:

“There is a very real problem of overcrowding which the Government has neglected. We are not having this immigrant question used as an alibi for the total Tory failure to handle the problems of housing, slums, schools and education in this country.”[8]

However, after the election the government set about tightening the controls.

Collapse

The Conservatives had enforced the Act fairly loosely – Commonwealth relations had to be managed and public opinion had to be nurtured. Once Labour gained power in 1964, however, restrictions were increased. From September work vouchers were only issued to people with firm job offers or specific skills. Such a policy favoured whites, as the working party in 1961 had suggested it would.[9] Vouchers granted were limited to 8,500 a year in 1965. Restrictions on dependants included “nephews and cousins and children over 16”:

“In future, dependants would be expected to produce either an entry certificate or appropriate documents to establish identity at the port of entry. This was the origin of the system of entry control which saw the posting – to those Commonwealth countries that were sources of immigration – of Entry Control Officers whose job was to validate evidence of identity and issue entry certificates.”[10]

During the ensuing period of Labour government, restrictions became tighter, to the point that in 1969 The Economist declared that Labour had “pinched the Tories’ white trousers”.[11]

In the next blog: when a “liberal agenda” masks “political cowardice”.

[1] Hayter, T. (2000), Open Borders: the Case against Immigration Controls, Pluto Press, London, p.46.

[2] Playing the Race Card, October-November 1999, Channel Four Television, London.

[3] Hayter, T. (2000), Open Borders: the Case against Immigration Controls, Pluto Press, London, p. 46.

[4] Foot, P. (1968), The Politics of Harold Wilson, Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, p. 252.

[5] Ibid., p. 254.

[6] Foot, P. (1970), The Rise of Enoch Powell, Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, p. 68.

[7] Playing the Race Card, October-November 1999, Channel Four Television, London.

[8] Hayter, T. (2000), Open Borders: the Case against Immigration Controls, Pluto Press, London, p. 50.

[9] Spencer, I. (1997), British Immigration Policy since 1939: the Making of Multi-Racial Britain, Routledge, London, p. 116.

[10] Ibid., pp. 135-6.

[11] Hayter, T. (2000), Open Borders: the Case against Immigration Controls, Pluto Press, London, p. 51.

Racist mission accomplished

Continuing the story from the previous blog: as we have seen, although governments and their officials dearly wanted to impose racist immigration controls right from the start, they hesitated. We will look at some more of the reasons and see how a Tory government finally got its wish, embodied in the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962. But it took that long. Here are some of the reasons.

The Commonwealth connection

It was not only the complications of “kith and kin” in the “white” Commonwealth that made governments delay legislation. The UK’s relationship with the Commonwealth as a whole was also a factor. In a period of decolonisation and the building of Commonwealth institutions, UK governments trod carefully. For example, openly discriminatory legislation “would jeopardise the future association of the proposed Federation of the West Indies with the Commonwealth”.[1] Politicians tried to persuade governments in the Caribbean and the Indian subcontinent to control the flow of migrants at source. They had some success in India and Pakistan, but not in the Caribbean. In 1958 Sir Henry Lintott, Deputy Under-Secretary of State at the Commonwealth Relations Office, advised caution on the question of legislation. There had been calls for immigration controls in the wake of the Notting Hill riots (provoked by extreme right-wing groups such as the League of Empire Loyalists). Sir Henry advised that in these circumstances immigration controls would imply that “the British people are unable to live with coloured people on tolerable terms”:

“This could be immensely damaging to our whole position as leaders of the Commonwealth which, in its modern form, largely draws its strength from its multi-racial character. If, therefore, strong pressure develops for the introduction of legislation to control immigration, I would hope that some way could be found to delay action and to permit passions to cool.”[2]

These arguments were supported not only by many in the Conservative Party in the mid 1950s but by the Labour Party too. In 1958 Arthur Bottomley spoke for the Labour front bench against legislation to control immigration:

“The central principle on which our status in the Commonwealth is largely dependent is the ‘open door’ to all Commonwealth citizens. If we believe in the importance of our great Commonwealth, we should do nothing in the slightest degree to undermine that principle.”[3]

With a House of Commons majority of only fifteen, the Conservative government was vulnerable. Similar considerations had applied in January 1955 when Home Secretary Gwilym Lloyd George presented his ideas for restrictive legislation to the cabinet. The cabinet judged that “such a bill would not obtain the full support of the Conservative Party and would be opposed in the House by the Labour opposition and outside the House by the Trades Union Congress.”[4]

The working party evidence

Another obstacle to immediate legislation was the fact that the working parties set up to provide evidence of the “undesirability” of black immigrants failed to do so. They described “coloured women” as “slow mentally” and said that their “speed of work” was unsatisfactory. They claimed there was “a disproportionate number of convictions for brothel keeping and living on immoral earnings” among West Indian men and made references to “the incidence of venereal disease among coloured people.”[5] But they failed to make the case for immigration legislation. The committee with the specific mandate to investigate “social and economic problems” relating to “coloured workers” must have been a particular disappointment. In August 1955 the committee’s draft statement went to the cabinet. The allegation of a high incidence of venereal disease was included here – but only as a “suggestion”. The author of the report admitted that there were no figures to support the claim. Spencer summarises the committee’s findings:

Although “coloured” immigration was running at the rate of about 30,000 a year … even those arriving most recently had found jobs easily and were making “a useful contribution to our manpower resources”. Unemployment … could not be regarded as a problem, nor could undue demands on National Assistance or the National Health Service … The immigrants were for the most part law-abiding except for problems with [cannabis] and living off the immoral earnings of women. Though the immigrants had not been “assimilated” there was no evidence of racial tension and it was apparent that some “coloured” workers in the transport industry had made a favourable impression.[6]

The same was true of the working party’s reports between 1959 and 1961. “Viewed objectively”, writes Spencer, “the reports of the Working Party consistently failed to fulfil the purpose defined in its title – to identify ‘the social and economic problems arising from the growing influx of coloured workers’. In the areas of public order, crime, employment and health there was little noteworthy to report to their political masters.”[7] Moreover, the Treasury, when asked whether black and Asian immigration benefited the economy, “gave the clear advice that on economic grounds there was no justification for introducing immigration controls: most immigrants found employment without creating unemployment for the natives and, in particular by easing labour bottlenecks, they contributed to the productive capacity of the economy as a whole.”[8]

But, in the end, the working party managed to construct an argument for controls.[9] “‘Assimilability’ – that is, of numbers and colour – was the criterion that mattered in the end.” Between 1959 and 1961 there were large increases in the numbers of blacks and Asians entering the UK. At the beginning of the period there were around 21,000 entries a year; by the end they had risen to 136,000 (though much of this last figure may have been due to the fact that the government had signalled its intention to introduce legislation and larger numbers had decided to come in order to “beat the ban”). Working party officials compensated for their inability to find existing problems by predicting that they would arise later:

“Thus in February 1961, whilst it was admitted that black immigrants were being readily absorbed into the economy, [officials predicted] ‘it is likely to be increasingly difficult for them to find jobs during the next few years’. Further, it was doubtful if the ‘tolerance of the white people for the coloured would survive the test of competition for employment.’”

There would be “strains imposed by coloured immigrants on the housing resources of certain local authorities and the dangers of social tensions inherent in the existence of large unassimilated coloured communities.” The working party recommended immigration controls. It was “prepared to admit that the case for restriction could not ‘at present’ rest on health, crime, public order or employment grounds” but

“[i]n the end, the official mind made recommendations based on predictions about … future difficulties which were founded on prejudice rather than on evidence derived from the history of the Asian and black presence in Britain.”

Now there was just one obstacle impeding the introduction of controls.

Public opinion